Inspiring Older Readers

posted on 20 Jun 2022

posted on 20 Jun 2022

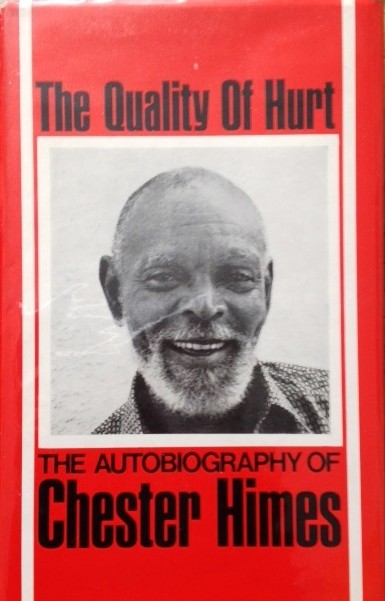

The Quality of Hurt by Chester Himes

Black American author, Chester Himes (1909 – 1984) is probably best known in this country for his hard-edged Harlem Detective series of books featuring two black policemen called Grave Digger Jones and Coffin Ed Johnson. Some of these novels have been made into films and you’ll find one of the biggest titles, Cotton Comes To Harlem reviewed on this site here.

The Quality of Hurt is Himes’ autobiography published in 1971 and covers the first 45 years of his life. And I have to say at the outset that I’ve never before read an autobiography quite like this. You may have heard the phrase ‘telling it warts and all’ when confronted with unexpected criticality and frankness but this takes it to a whole other level. This is warts and all with an extra helping of warts.

The hurt Himes alludes to in his title is multi-layered but this is a man consumed by anger that has its origins in the structural racism of the country he was born in and where he lived until he simply had to breakaway and find a home in Europe – primarily in the French capital, Paris.

The details of his life are so extraordinary and so explicitly recounted that you have to keep reminding yourself that you’re not reading one of his novels. He was born into what was effectively a middle class family in Missouri where his father was a professor at a black college and his mother was a teacher. Himes was especially close to his brother Joseph and felt himself implicated in a tragic accident that would blind his brother and ‘hurt’ Chester like no other event. When Joe was mixing chemicals for a demonstration at a school assembly it suddenly exploded in his face and it was clear that he needed urgent hospital treatment but, being black at a time when the Jim Crow laws were in place meant they were turned away from the nearest hospital and had to hunt for a hospital that would take black patients – that delay was critical and Joe’s sight couldn’t be saved.

This seemed to bring Chester’s rage to a continual boil and his life became a litany of law-breaking until he was eventually imprisoned for the especially inept jewellery robbery of a rich white family. It was during this time of imprisonment that he started writing and submitting his work to a range of periodicals.

By this point in the book I was starting to find the whole raging hurt issue quite tough to handle. Himes uses it as a bludgeon with everyone he met – especially women – and his self-confessed (unapologetic) abusive violence towards the women who get close to him and his sneering contempt for them is hard to stomach.

When he eventually decides to leave his wife Jean and that racist America isn’t a place he can live any more he uses his connections with other exiled black American writers – most notably Richard Wright - to try finding a new home in Paris. It was here that he met his second wife, Lesley, a magazine feature writer who Himes was destined to stay with until his death in 1984 – but that is not covered by this first part of his autobiography and would have to wait until part two which was later published in 1972.

This book is quite a read and not one to take on if you like your autobiographies to be gentle reminiscing. This is a full-on punch in the gut from a man who, although undoubtedly talented as a writer, must have been an absolute nightmare to spend time with. However, if you want to get a flavour of what structural and casual racism can do to a life, take a look at this even if you find it hard to stay with.

The book is quite hard to find and is, I’m pretty sure, out of print. You can find it on dedicated second hand websites but you’ll need to pay over £20 in all likelihood.

Terry Potter

June 2022