Inspiring Young Readers

posted on 06 Aug 2016

posted on 06 Aug 2016

Separated by a common language : children's books I didn't grow up with

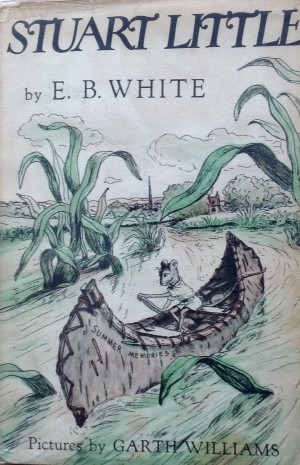

I recently picked up a copy of E.B. White's children's story, Stuart Little and looking at some of the critical assessments and promotional puffs for it that you'll find on the internet it is clearly what the publishing industry like to call a 'beloved classic' - a book that is or should be part of every American child's upbringing. It's a short book, nicely illustrated by Garth Williams, of loosely associated adventures of a rather dapper little mouse born into an otherwise normal human family in New York. Like all good children's books it doesn't try to explain how this has happened, how this mouse child can talk or why his parents seem to take his mouse-ness in their stride.

Pleasant enough as this little tale is, it made me think about how I had never really came across White's creation until it found its way onto film. And, expanding on this line of thinking, I realised that quite a number of American childhood classics were never part of my, or my generation’s, upbringing nor was I ever aware of them in the general cultural environment I inhabited.

'Curious George', most of Dr Seuss, The Little House on the Prairie, Anne of Green Gables, Charlotte's Web and even Little Women were either unknown when I was young or strangely exotic if you did come across them. Even the prolific talents of Maurice Sendak or Eric Carle would not come within my orbit until I was well into my adult years. It felt as though American children's books were written in a foreign language and coming from an alien culture that didn't really speak to British children, or at least not to post-war, working class children from Birmingham.

I’m pretty sure that most of my peers would never have come across these American classics either but it made me wonder what changed this and lowered these cultural barriers – because today’s children seem to make little distinction between British or American books and the characters they contain. I can’t help but feel that the key factor seems to have been television and movies. Where the books were oddly invisible to us, the moving image made the stories and characters accessible - even when we didn't know the programmes or films were based on books. Television programmes, series and films using classic American children's literature as its inspiration seemed to proliferate dramatically from the mid-1970s onwards and it seems logical that it would have played an important part in creating openings for the books themselves to be more aggressively marketed.

And, going back to the example of Stuart Little, I think we can see why film and t.v. might have played such a key role. Children's books are, by their nature, very visual - to appreciate Stuart's adventures you really need to have an idea of what 1940s New York might have looked like and why Stuart bowling along in his own little car or being ferried off in a garbage truck might thrill an American child. Film, of course, does this hard work for a child who has no concept of New York.

Equally, whilst White's language is magnificent - he was a master stylist - his lexicon is American and he knows exactly what the American child will understand and respond to. He also includes several whimsical asides clearly aimed at the adult who is likely to be reading the book with their child. All of this otherwise difficult-to-understand stuff can be dealt with, edited and homogenised, for a film audience that is international and which would not understand the cultural specificity of America in the years immediately after World War Two.

So I can’t help but think film and television have done young readers a great service. Where my generation had no real access to American children's literature and would have found it difficult to crack the 'code' that would have given us an understanding of the books and the world the characters in the books lived in, children can now select their books safe in the knowledge that television, film and the internet have provided the necessary landscape and language to make sense of them.

Terry Potter

August 2016