Inspiring Young Readers

posted on 06 May 2016

posted on 06 May 2016

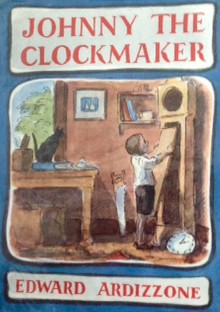

Edward Ardizzone

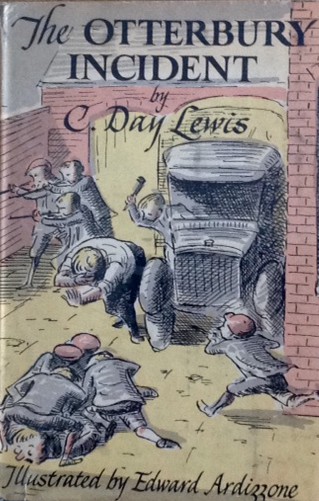

I first became aware of Edward Ardizzone’s work as an illustrator of children’s books when I bought a hardback copy of C. Day Lewis’ The Otterbury Incident well over twenty years ago. The engaging pen and colour wash illustrations seemed just perfect and yet, deceptively simple – maybe something anyone could do – and yet they were filled with atmosphere and, curiously, seemed able to catch small inflected facial expressions in a way that made it immediately obvious that this wasn’t the work of an amateur or second-division talent.

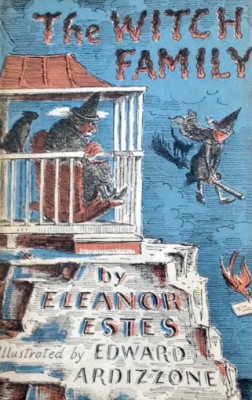

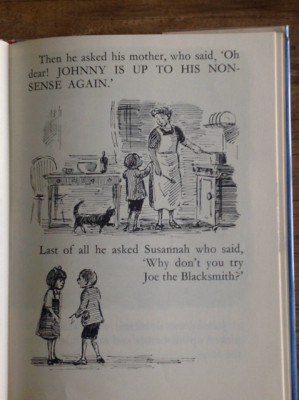

In fact, as I explored more of Ardizzone’s work it became clear that I’d been seeing him everywhere but I just hadn’t been noticing. A whole range of children’s books published by Puffin and plenty of older hardback children’s classics all carried illustrations by him – some in colour but lots of them in that characteristic black pen – drawings that seem to comprise of nothing but lines, shading and cross-hatching which somehow resolve themselves into a perfect little vignette.

Ardizzone was born as the 19th century turned into the 20th with a curious heritage – his father was a French national born in Algeria but with Italian roots – and having started life in French Indo-China, Edward and the family settled in England in 1905. He looked as if he was heading for a respectable but mundane life as an office clerk but his desire to be an artist won through and – to the horror of his family – he gave up work in 1927 to concentrate on his art.

By the 1930s Ardizzone was becoming a substantial and recognised artist with exhibitions of his own and a family man - married with children to think about. Ardizzone’s creation of Little Tim – probably his most famous sequence of children’s books – is sometimes attributed to the influence of his children demanding that the stories he was telling them should be turned into drawings and put in books.

Of course, for any artist, earning money is a struggle and so illustrating the work of other writers is a godsend if you can get the work – and Ardizzone was, by this time, becoming a popular choice for publishers to turn to. However, the start of the Second World War had a big impact on the art that Ardizzone would produce over the duration because in 1940 he was appointed as an official war artist – initially going across to France but spending time also recording the home front. He had further postings abroad before the war ended and by the mid-1950s he had become a major part of the art establishment.

He continued working as a both an artist and children’s illustrator – developing the Tim series and adding new creations of his own – until his death by heart attack in 1979.

I’m not sure how appealing Ardizzone’s style is for children today but I’d like to think that they can still see the subtle craft that lies behind the seemingly simple style. Ardizzone was incredibly prolific and so there is plenty to choose from when it comes to finding the style that best suits you but, for me, he never did better work than for the Tim books. The stories themselves are disarmingly simple but full of adventure and although Tim and the other characters that populate the book seem to be representatives of a mid-twentieth century England that has disappeared into history, they are still identifiably ‘every-child’ in the sense that it’s so easy to identify with Tim’s travails and successes.

It’s relatively easy to get hold of the Tim stories in more recent reprints but I have to say that they don’t come close to the richness of the originals which have an almost painterly presence on the page. Still, having them is better than not having them. You’ll also find plenty of Ardizzone’s work as an illustrator in lots of second hand book shops – he did end up illustrating over 170 books - although some of his first editions are now getting very pricey.

There is a very nicely done Edward Ardizzone website which contains a list of his own books that are currently in print and some links to useful other reference books. Take a look – it’s a great place to start exploring his work.

Terry Potter

May 2016