Inspiring Older Readers

posted on 24 Aug 2025

posted on 24 Aug 2025

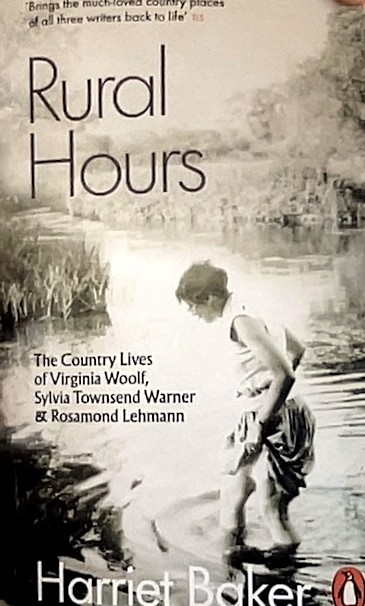

Rural Hours by Harriet Barker

After what seems like weeks I have finally finished Harriet Barker’s Rural Hours: The Country Lives of Virginia Woolf, Sylvia Townsend Warner and Rosamond Lehmann. When I bought this it was with some trepidation because my tolerance for books about ‘country life’ is low. But this is a book about a trio of writers whose lives and work are fascinating and I admire biographical books that take on the intertwined lives of a number of figures in order to illuminate a place or period, as this one does, so I thought I really ought to give it a go.

In the first half of the twentieth century it does seem that English rural life exerted a strong pull amongst a wide range of cultural and intellectual figures in a way that cannot be entirely explained simply by the desire amongst the well-off for rural bolt-holes in which to escape the clamour of city life, although without doubt this was a motivation for some. From around 1917, Virginia Woolf, for instance, divided her time between London and Asheham House, a small cottage in the Sussex village of Beddingham. Initially, this was a means of escaping the city during the Zeppelin raids of the First World War but it also meant more: ‘I believe our half in half existence is ideal,’ she wrote to a friend: ‘…a taste of people, and then a drench of sleep and forgetfulness, and then another look at the world, and then back again.’ Sylvia Townsend Warner and her lover Valentine Ackland, found that the country offered them a respite from the kind of censorious scrutiny that their lesbian relationship would be subject to in town. Rosamond Lehmann was fleeing a collapsed marriage and the London Blitz, seeking a safe, independent refuge for herself and her two children. I think other commentators on the period talk about a rediscovery of an English pastoral tradition in the wake of the First World War, especially amongst visual artists and writers, and there does seem to be an element of this too.

What Baker does make a convincing case for, I think, is the real and lasting impact rural life had on the work of these women writers. Sylvia Townsend Warner’s first novel, Lolly Willowes, for example, explicitly draws on country lore and the role of women and magic. The minutiae of country household accounts also interested her and in the longer historical novels she wrote later in life – The Corner that Held Them, for instance, her novel of life in a medieval nunnery – she rigorously scrutinised these domestic finances in precisely the way she believed that diligent Communists, which at that time she was, should analyse ‘economic causes’. Rosamond Lehmann drew deeply on her own experience of life in the country during the years of the Second World War with a series of increasingly sophisticated short stories. Woolf made perhaps more oblique use of her ‘rural hours’, but they can be traced in the rural settings of some of her fiction and in the way that her voracious country reading prompted her to write marvellous essays and occasional pieces about naturalists such as Gilbert White, eighteenth century diarists, minor Elizabethans and forgotten country clerics. Her ‘rural hours’ sometimes seemed a way of resurrecting the past.

I finished this book immensely better informed about the writers it discusses, while not necessarily liking them more, its gallery of resolutely upper class characters sometimes difficult to have sympathy with. Now and then I had to remind myself that they were important precisely because they were conscious of their privilege and were seeking ways to rebel against it. In any case, railing against privilege in upper class literary circles is pointless: it can’t be retrospectively corrected and in a sense you have to regard it historically and concentrate instead – as Sylvia Townsend Warner almost certainly did – on understanding its causes and consequences.

But I also found the book far more moving than I expected to, especially its handling of Virginia Woolf’s death, the tragedy of Rosamond Lehman’s later life, and Sylvia Townsend Warner’s indomitable stoicism. In fact, I think STW (as I chummily began to think of her) may well be the one figure that I did end up thinking more highly of.

But most of all I was in awe of Barker’s scholarship and the depth of her research and contextual reading. For in addition to fiction, her subjects were also prolific essayists, letter-writers, diarists, and journal-keepers and such a wealth of background sources needs to be used elegantly and lightly and fluently if the narrative is to avoid sagging under its own weight and Barker achieves this brilliantly. And perhaps most significantly, she restores these ‘rural hours’ to a position of central importance in her subjects’ lives, as crucial and as formative as anything else in the turbulent century that they lived through. It is a stunning achievement and I’m glad I stuck with it because it also turns out to be hugely enjoyable.

Alun Severn

August 2025

Similar ‘intertwined’ biographies elsewhere on Letterpress:

Square Haunting: Five Writers in London Between the Wars by Francesca Wade

Ravilious & Co: The Pattern of Friendship by Andy Friend

Magnificent Rebels: The first Romantics and the invention of the self by Andrea Wulf