Inspiring Older Readers

posted on 25 Jun 2025

posted on 25 Jun 2025

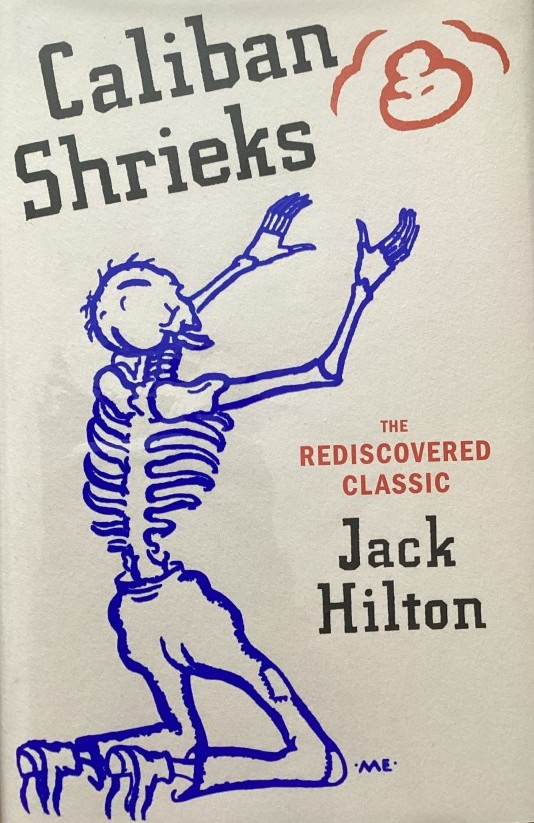

Caliban Shrieks by Jack Hilton

I’ve commented before in previous reviews for this website, that it’s a puzzle to me just why some authors and their books continue to thrive over the decades while others, mysteriously, slip from view regardless of their quality. But the case of the working class author, Jack Hilton (1900 – 1983), takes this mystery to a whole other level because his five books have literally become completely unavailable in their original editions: they must be out there somewhere but you’ll try in vain to track one down on an internet that usually turns up the rarest of the rare.

His 1935 ‘novel’ Caliban Shrieks has finally been republished in this 2024 Penguin edition thanks entirely to the tenacity of Jack Chadwick, who happened upon the book on the shelves of the Working Class Movement Library in Salford and faithfully transcribed the text. The remarkable story of how Caliban found its way back into the light is detailed in the forward written by Chadwick – and a fascinating read that makes in its own right.

Hilton was one of several working class writers who, in the mid-1930s, was given a break by The Adelphi magazine – a left-wing literary publication that included the likes of George Orwell in its roster of writers. As a result of this camaraderie, when Hilton moved on from single articles to something approaching a coherent novel with Caliban Shrieks, Orwell agreed to review it – and it became the first review done under Eric Blair’s pen-name of George Orwell.

You will perhaps have noticed that earlier on I put the description of the book as a novel in inverted commas because, in genre terms, it’s almost uncategorisable: some part autobiography, some part dramatic fiction, some part sociology, some part stream of consciousness. What it is, I think, is exactly what Hilton said – an unmodulated shriek of rage and despair on behalf of so many working class men who find their lives bent out of shape by powerful ‘masters’ (hence the allusion to the themes of Shakespeare’s The Tempest).

Orwell plumped for calling it ‘an autobiography without narrative’ and you can add to that the fact that it is almost devoid of any description. What we get is a loosely linked series of episode and vignettes which, as Richard Young writing on the Orwell Society website, describes this way:

“In avoiding excess description he takes instead a polemical approach to ram home the messages he wishes to deliver on harsh working conditions, lack of job security, inadequate social protection, fragmented political representation on the left, and poverty.”

What Orwell puts his finger on his review is that this book feels different to some other books that document the plight of the working class in the 1930s because Hilton wants to tell us how it feels from the inside – his response is visceral because he’s living it not stepping back and looking at issues from a distance.

Orwell judged that:

“Books like this, which come from genuine workers and present a genuinely working-class outlook, are exceedingly rare and correspondingly important.”

The book is emotional, raw and at times feels almost incoherent with rage but I certainly go along with Orwell’s view that these voices are important to have out there – the fact that Hilton’s work had been airbrushed out of history until now is outrageous and so we should all tip our hat to Jack Chadwick’s determination to get it reprinted.

Currently available in hardback but not expensive to find on secondhand book sites and should cost you little more than £10 for a good copy.

Terry Potter

June 2025