Inspiring Older Readers

posted on 18 Jun 2025

posted on 18 Jun 2025

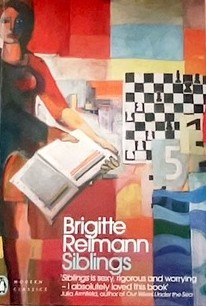

Siblings by Brigitte Reimann

First published in 1963, Siblings is the work of a young woman writer and later painter, Brigitte Reimann, an East German socialist (but not a Communist Party member), living in the then-German Democratic Republic (GDR). She was born in 1933 and died dreadfully young in 1973, aged just 39. At its heart it is a novel about the impact of totalitarian political systems on family relationships and personal freedom and the decisions its central characters – Elisabeth Arendt, a young woman in her early-twenties, a painter (essentially Reimann), and her two brothers, Uli, the younger, and Konrad, the older, the siblings of the title – have to make.

Both brothers, for differing reasons, decide to defect to West Germany. In the case of the older bother, his reasons seem essentially materialistic: he wants a better, more westernised lifestyle for himself and his glamorous girlfriend, with all the access they dream of to luxury goods and Western fashions. In the case of the younger brother, his reasons seem more complex: he is against the regime not because he is opposed to communism but because he believes that the East German Communist Party is betraying the very freedoms it should protect. Elisabeth, probably best described as a socialist who is loyal to the emerging socialist state but unable to submit to the rigours of party discipline, is similarly idealistic. Her bohemianism and her insistence on a sensual life as well as a cultural and political one put me in mind of revolutionary feminist socialists of the Bolshevik era such as Alexandra Kollontai and Rosa Luxemburg. I would be reasonably confident that this would have been the kind of lineage Reimann herself would have acknowledged.

The novel is told in short often intensely described vignettes and has – as one reviewer pointed out – something of the feel of street photography; it also made me think of new wave cinema – swiftly rendered dramatic scenes that sometimes have a slightly cryptic self-sufficiency about them which require you to make your own interpretation. But what I think is most unusual about this novel is that it is political fiction written by a young woman in her twenties, who was not a dissident in any conventional sense of that term but who was uncompromisingly rebellious and nonconformist while also writing from within the structures of the East German political system. Like Elisabeth her narrator, Reimann was a writer and painter and central to her young experience was the period she spent as a sort of artist-in-residence at a brown coal industrial plant. This policy, known as the Bitterfeld Weg (the Bitterfield Path), was intended to bring artists and workers together and ensure greater adherence to the ‘party line’ of socialist realism in the arts.

The main problem with the novel, I think, is that it tries to do more than its scarcely 120-pages can achieve and with a bit more length it might have been more fully realised. The other consideration, I suppose, is that when Reimann wrote the novel neither she nor any other writers of that period could possibly have conceived of a time when the inner workings of Eastern bloc communism would need to be explained for the modern reader. Thankfully, the translator, Lucy Jones, does a good but light-touch job of providing just enough in the way of footnotes to clarify some of the more obscure aspects of the text.

I won’t spoil what relatively little plot the novel has by giving away the ending. While ultimately I found it slightly disappointing, it has been a long time since I last read a work of fiction that in itself doesn’t really succeed but by way of compensation offers much more that is of interest. I think anyone who wants to know more about life under Soviet-era Eastern bloc communism – especially the life of younger people – will find it fascinating.

Alun Severn

June 2025