Inspiring Older Readers

posted on 02 Jun 2025

posted on 02 Jun 2025

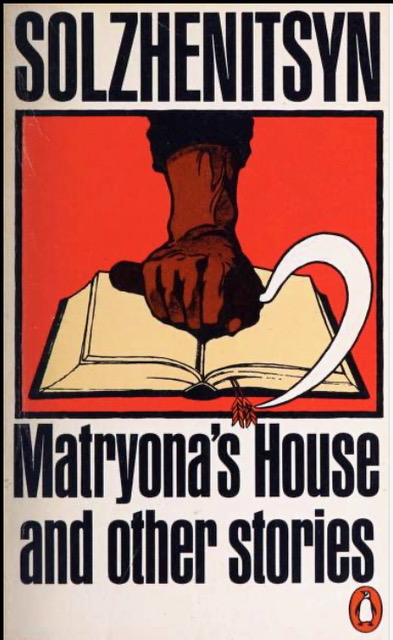

Matryona’s House and other stories by Solzhenitsyn

Back in 2019 I reread J.L. Carr’s A Month in the Country (reviewed here) and I was surprised to find that in her introduction to the Penguin Modern Classics edition Penelope Fitzgerald said that the intensity of its depiction of rural atmosphere reminded her of Solzhenitsyn’s short story, Matryona’s House. I remember thinking that perhaps only Fitzgerald would make such an unlikely connection. A couple of weeks ago I finally got round to rereading that early Solzhenitsyn short story.

Even before I opened the book I was whisked back in time to when I first began to see this iconic cover (pictured) appearing on bookshop shelves in the very early-70s. I remember registering that the cover was designed and illustrated by someone called David King, and although it would be years before this meant anything to me, I began to notice his name on covers for Penguin and other publishers. King, who died suddenly in 2016, is now widely acclaimed as a graphic designer, photographer, writer and archivist, as renowned for the gigantic collection of Soviet-era material he amassed and for his graphic design for numerous radical and left-wing campaigns throughout the 70s and 80s as he is for his commercial design work. His entire archive has now been acquired by the Tate.

This explains very little about Solzhenitsyn’s story, I realise, but perhaps does help to explain the mysterious process whereby some books become associated with a sort of hinterland of memories and associations which render them all the richer and all the dearer to us. Anyway, back to Matryona’s House. It is 1953. Ignatich, the narrator, is a former prisoner and a maths teacher who is trying to find work and lodgings after his release from a lengthy prison camp sentence, his return from the ‘hot, dusty wastelands’ delayed, he says with mild irony, ‘by a little matter of ten years’ (presumably an additional sentence imposed for some infraction or other – not uncommon in Stalin’s gulags). It is also likely that Ignatich’s release has been occasioned by Stalin’s death in early-March of that year.

Ignatich has made his way to the tiny rural hamlet of Miltsevo. After failing to find lodgings in several places, he is referred to Matryona, a widow who lives in what was once a pleasant dacha-style house, built some thirty or forty years earlier, now dilapidated and infested with vermin, but nonetheless comfortable. Matryona herself is tirelessly active, collecting peat to fuel the stoves through the appalling winter cold, digging potatoes or collecting berries, shopping or bartering for food, endless futile trips to various administrative offices in pursuit of her pension, work at the local collective farm, the occasional visit to see neighbours.

Ignatich decides that lodgings with Matryona will suit him very well. While he recognises that her eccentricities and superstition and narrow experience may well drive him to distraction, nonetheless he admires and respects Matryona and acknowledges her importance in the tiny rural community he gradually comes to regard as home. Her life has been punishingly had and has involved much suffering, but within the confines of her essentially peasant morality she has always tried to do the right thing and to do good. She may in some sense even be a ‘Mother Russia’ figure.

What makes Matryona’s House extraordinary, I think, is that the rural life it depicts is not unlike that which we see in Turgenev or Chekhov. This reflects Solzhenitsyn’s commitment to the humanist values of the realist masters, but it also constitutes his slyly subversive central message: that despite revolution, collectivisation, Stalinism and world war, rural Russia remains a stubbornly nineteenth century society.

J. L. Carr’s A Month in the Country recalls a benign, restorative, even idyllic, rural life, whereas the rural life depicted in Matryona’s House is punishingly harsh and – as we intuit from the foreboding opening of the story – destined to end in tragedy. Clumsiness, greed, ignorance and drunkenness, an isolated rural society which was never going to join the ranks of Stalin’s ‘New Soviet Man’ – the affinities with nineteenth century literature become stronger the more one considers the story. I haven’t yet gone on to read all of the other pieces in this collection because I have never managed to convince myself that they will live up to the vivid detail and utterly believable realism of Matryona’s House. It may not have the huge ambition of Solzhenitsyn’s greatest novels – of First Circle or Cancer Ward, for instance – but this short story has a quiet grandeur and a depth that nonetheless place it amongst his finest work.

Alun Severn

June 2025

Solzhenitsyn elsewhere own Letterpress:

One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich by Alexander Solzhenitsyn (Sept 2024)

One Day In The Life Of Ivan Denisovich by Alexander Solzhenitsyn (trans. Ralph Parker) (Nov 2016)

More elsewhere about David King’s life and work: