Inspiring Older Readers

posted on 25 May 2025

posted on 25 May 2025

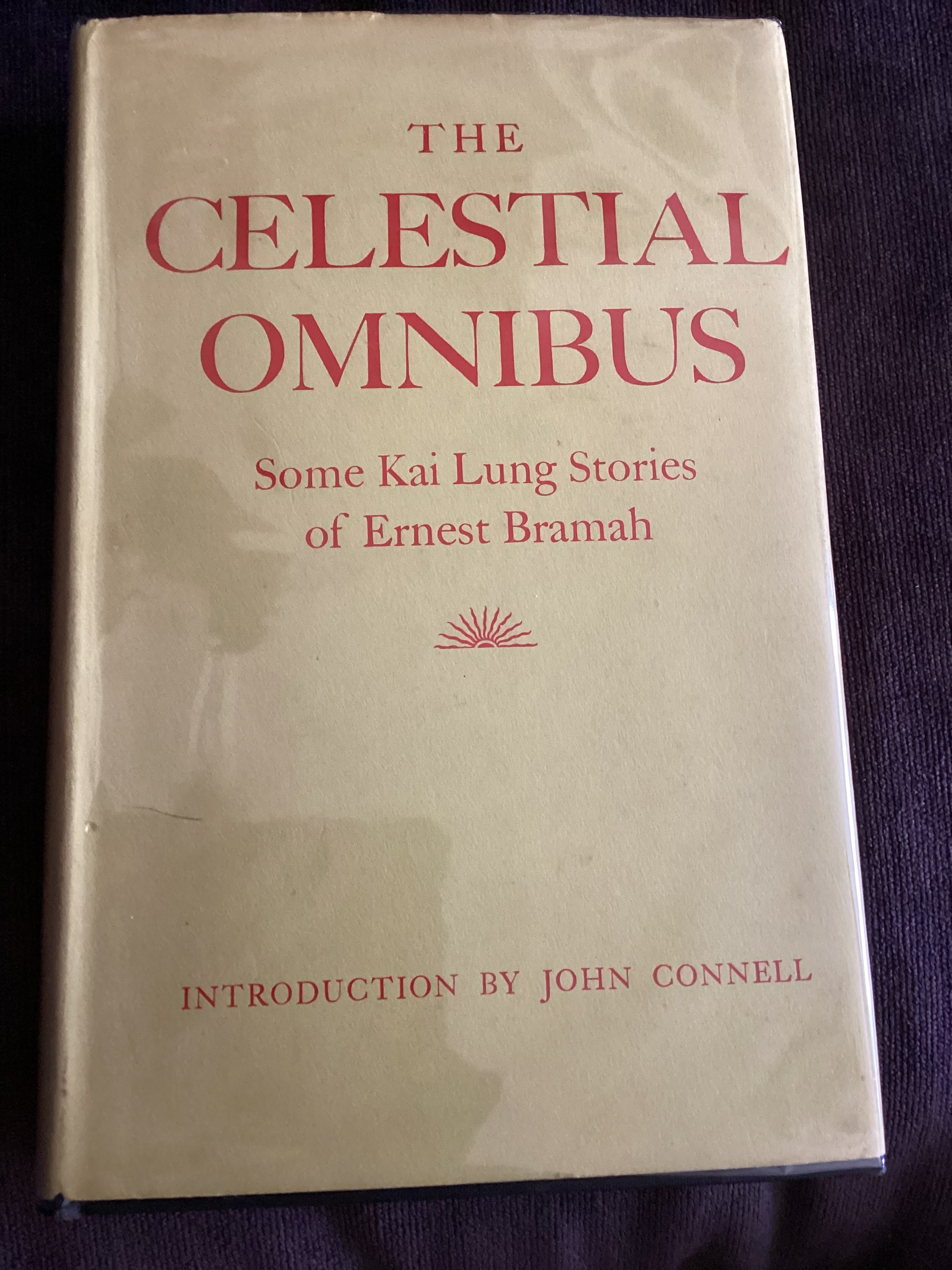

The Celestial Omnibus by Ernest Bramah

When I stumbled on this book in a second-hand shop, it was the name Ernest Bramah that caught my eye and persuaded me to pick it up, leaf through it and buy it – out of sheer curiosity. The name Bramah was familiar to me because back in 2021, I had read and reviewed a book of his in the Penguin crime series called The Max Carrados Mysteries and so I knew that the author had an intriguing back-story.

However, ‘intriguing’ as a description probably does him a significant disservice – odd or eccentric might be a better pair of adjectives. Ernest Bramah was the pen name of Ernest Brammah Smith (1868 – 1942) who dropped out of Manchester Grammar School to become a farmer – an enterprise funded by his father – and almost immediately started writing and submitting vignettes of country life for publication and on the back of this literary ambition he became, for a while, secretary to Jerome K. Jerome.

Bramah, it seems from most biographical sources, turned into something of a recluse and this added to the air of mystery surrounding him. Oddly enough, he also wrote a science fiction/speculative fiction novel that is often credited on the internet with being an ‘influence’ on Orwell’s writing of 1984 – although this rumour has been effective quashed by The Orwell Society in an article you’ll find here.

In fact, Bramah was almost certainly right-wing in his political opinions – something which rather shocked and dismayed Orwell given that he was generally well disposed to his sequence of Max Carrados stories.

But although the detective novels have retained some kudos amongst crime aficianados, Bramah actually first hit pay-dirt with another series of tales presented as if written by the fictional Chinese storyteller, Kai Lung – and it is selections from these books that make up The Celestial Omnibus. In an article entitled Ernest Bramah: Crime and Chinoiserie, David Langford captures them perfectly:

“Kai Lung came first. The Wallet of Kai Lung crept imperceptibly into print in 1900; like all Bramah's best work it consists of short stories. In this series they're normally fantastic tales related by the itinerant Kai Lung in an exceedingly mannered "Chinese" idiom. (As regretfully noted in The Listener's 1947 retrospective article on Bramah, it seems pretty certain that he never left Europe, let alone visited China.) Occasionally the teller is dispensed with, but the voice remains the same.”

I have to confess that David Langford seems to have had a lot more success reading this tosh than I did because I only managed half of one long short story before it almost drove me to throw the book out of the window. The cod-ancient Chinese seer persona and the ridiculously convoluted Fu Manchu-esque sentences left me just plain embarrassed.

I find it almost impossible to understand how or why this became a favourite read for so many – but it did. This popularity is reflected in the New York Times obituary of 1942:

“Possibly it may take a little application to acquire a taste for Ernest Bramah’s style, for the flavor is odd and unexpected and highly individual. The taste, once acquired, is apt to remain with one. To those who remember “The Wallet of Kai Lung’ or ‘Kai Lung’s Golden Hours’ there is little point in trying to describe a style which is bound to remain indescribable in any case.

To those who have never sampled it before, it may be said, perhaps not very helpfully, that it is a strangely variegated mixture of P. G. Wodehouse, Charlie Chan, the maxims of Confucius, and the Japanese schoolboy, with a good deal left over that must be pure Bramah.”

So, maybe it’s me that’s out of the loop here and I've badly under-estimated these tales? I'm willing to bet there will be more who agree with me than disagree but there’s only one way to find out: go and read some for yourself. I admit they aren’t too easy to find and it will probably mean a bit of hunting around on the internet. You can decide whether it was worth the effort and expense.

Terry Potter

May 2025