Inspiring Older Readers

posted on 20 Aug 2023

posted on 20 Aug 2023

The Beast in the Shadows by Edogawa Rampo

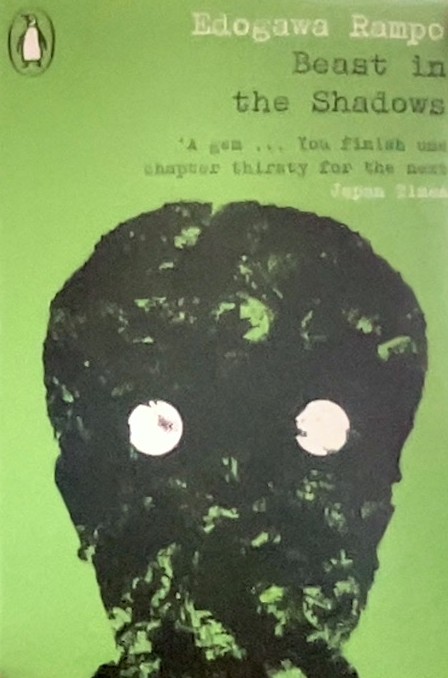

Recently I stumbled across the news that Penguin has launched a new Crime & Espionage series. I don’t read very much crime but I was immediately hooked by the terrific cover designs. Essentially, it is a relaunch of Penguin’s old ‘greenbacks’ crime series, nearly forty years after it was discontinued. Over the years I have collected dozens of these old titles and I always feel reassured that they are there on the shelves for when I feel I want some nostalgia-fuelled light reading.

The new series is slightly confusing because in some cases perfectly good versions of some of the first titles are already available in Penguin Modern Classics and at first glance this makes it look little more than a cynical marketing exercise. But in fact it is more than that: there are some genuinely interesting and unusual titles being published and the clever and often beautifully designed covers respectfully acknowledge the Penguin heritage.

One of the rarities must be Edogawa Rampo’s The Beast in the Shadows, which I just finished reading. Now, I’m hopeless at working out whodunnits and don’t usually even try; but I do enjoy reading crime novels for their atmosphere and settings, and on this score The Beast in the Shadows delivers generously.

Born in 1894, Edogawa Rampo was a prolific Japanese crime novelist, considered by some to be the founding father of Japanese crime writing. He died in 1965. The Beast in the Shadows was first published in 1928 but you would never guess this from the text: it is curiously, presciently modern, even postmodern. Its narrator, Kôichirô Samukawa, is a writer of detective stories who becomes involved in a real murder case. The book is made up of the notes he says he may need if or when he ever manages to use this baffling case as the subject of a new novel.

Right away, this felt to me like Italo Calvino territory – a book within a book, an enigmatic narrator, a murder story within a murder story, a reflection on the art and method of crime writing. Combine this with the febrile atmosphere and strange sensibility that Japanese literature often has (especially that of the 1920s and 30s) and add a distinct whiff of perverse eroticism and you have a heady mix – all packed into a book that is only a hundred pages long.

Anyway, one day in early autumn Samukawa, the detective novelist/narrator, goes to the Imperial Museum at Ueno to see the ancient buddhist sculptures. The hushed halls and cavernous galleries are almost deserted. But he is approached by a woman. ‘I was standing in front of a display case in one of the rooms,’ he writes, ‘gazing at an aged wooden bodhisattva that had a dreamlike eroticism. Hearing a muffled footfall behind me, I sensed someone approach with a light sound of swishing silk.’ This is Oyamada Shizuko, a pale and captivating beauty, the young wife of a local businessman.

She professes that she is a great fan of his novels, while he finds her bewitching – a young woman of ‘refined taste’ who visits ‘deserted museums’ on her own and who is devoted to his detective fiction (which some consider, the narrator notes with satisfaction, ‘the most intellectual in the genre’.)

But it turns out that Shizuko has a much stranger and more disturbing reason for approaching the narrator. She is receiving death threats from a former lover, a strange, misanthropic man called Oe Shundei, also a crime writer (but a ‘deviant type’, the narrator says dismissively). Shizuko thinks that only the narrator will understand her circumstances and he of course is only too eager to agree. After getting a journalist friend to help him investigate, he tells Shizuko that there is no further danger – Oe Shundei has completely disappeared. But within days, just as the letters from her former lover have threatened, Shizuko’s husband is murdered.

While I was slightly disappointed by the ending, I loved this novel for its deft humour and its rich atmosphere – the fascinating glimpses it offers into Japanese aesthetics and sensibility, its preoccupation with flawed beauty and the transience of the passing world, its allusions to patina and ageing, the melancholy of crepuscular evenings and the beauty of primitive rural retreats. For a crime novel from the late-1920s it is decades ahead of its time. At times it even made me think of Junichirō Tanizaki’s beautiful little essay about Japanese culture, In Praise of Shadows (reviewed here).

If the new Penguin Crime & Espionage series can continue to bring crime, espionage and noir classics to a new audience while also republishing brilliant neglected oddities like The Beast in the Shadows it will certainly be worth watching. There is a second Edogawa Rampo title due in October.

Alun Severn

August 2023