Inspiring Older Readers

posted on 27 Jul 2022

posted on 27 Jul 2022

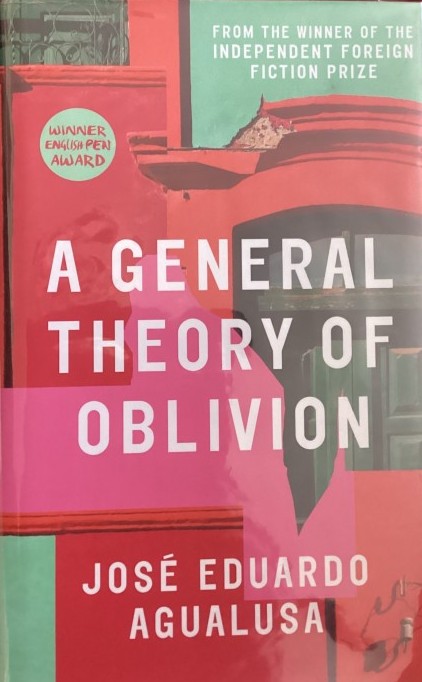

A General Theory of Oblivion by Jose Eduardo Agualusa

Born in 1960, Agualusa is an Angolan novelist who uses his fiction to explore his country’s long and troubled colonial relationship with Portugal. A General Theory of Oblivion, translated by Daniel Hahn, was something of a breakthrough novel in terms of readership in Britain and it went on to win the International Dublin Literary award - and some rave reviews from critics and literary commentators. It’s a powerful and poetic read that’s laced with often shocking, even brutal events that bring the social and political reality of violent revolution into the shrinking world of those associated with colonial rule.

The story is, apparently, based on a true story and focuses on Ludo, an agoraphobic Portuguese woman who moves to Luanda - the capital of Angola - with her sister and her husband. As the struggle for independence from Portuguese rule moves to its conclusion and violence begins to touch everyone, Ludo’s sister and husband disappear and she barricades herself in the flat, finding increasingly ingenious ways of keeping herself alive but effectively disappeared from everyone else. Once she has bricked-up the doorway it’s as if the flat doesn’t even exist.

From this vantage point she watches the world that goes past her window but has no real idea what’s happening on the outside other than what she picks up from a radio and through the overheard conversations of her neighbours.

She maintains this state of ‘oblivion’ for the best part of thirty years until her isolation is ended by Sabalu, a young boy who clambers through the window looking for easy loot. What he finds, however, is the old woman who has had a fall and broken her leg. Ludo insists that she will not have a doctor or go to hospital and so Sabalu ends up giving her whatever painkillers he can find and, ultimately caring for her.

It’s through this interaction that Ludo starts to piece together what has happened during the time she’s been holed-up in the flat. We also begin to discover the trauma in her early life that had triggered Ludo’s agoraphobia. Agualusa attempts to draw parallels between this woman’s experiences and the impact colonisation has on a country and its population. And, just as Angola has to break free of its past to emerge blinking into the light of the modern day, capable of looking after itself, so Ludo will now - he suggests - need to move on from her own self-imposed isolation.

Matthew Lecznar reviewing the book for africanwords.com notes the richness of the prose in what is quite a short book:

“Although a relatively short book at 243 pages, every character is richly portrayed, and the text is embellished with fragments of poetry and Ludo’s own writing. Each new chapter adds a further layer of narrative and meaning that both resonates with what has come before and unexpectedly reconfigures it, creating a shifting, organic tale.”

And language is a critical part of the book as we hear Ludo’s thoughts and get snippets of her increasingly eccentric diary. Control of language, Agualusa seems to be saying is key to understanding the relationship that exists between the abused and the abuser - colonialism at both a personal and national level. Memories can only be expressed in the form of language and language can be a slippery thing. Again Lecznar makes this point:

“The book as a whole is preoccupied with trying to discover deeper meaning in painful memories and ordeals, and with the potential for mistakes and misinterpretation to offer more profound truths than what is assumed to be correct. At one point, Ludo thinks she has gone mad when she sees Fofo the hippo on a neighbour’s veranda, and describes the experience of reading with failing sight: “I get things wrong, as I read, and in those mistakes, sometimes, I find incredible things that are right.” The reader is also involved in this process of interpretation and invention, being challenged at one point to think of a better word than “heart” to explain a person’s deepest desires.”

I found the book a tremendous but intensely claustrophobic read but it certainly sent me off to find out more about Angola’s troubled 20th century history.

Copies of the book in paperback are readily available both new and second hand and they won’t cost you the Earth. Hardbacks - especially of the first edition from 2015 - come at a much higher price.

Terry Potter

July 2022