Inspiring Older Readers

posted on 16 Jan 2022

posted on 16 Jan 2022

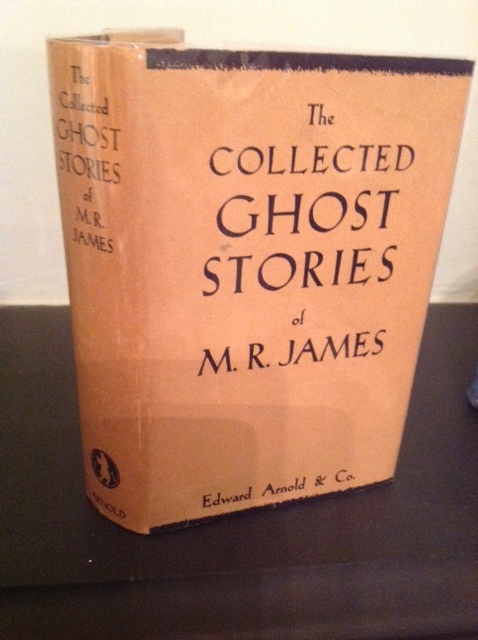

Rereading M.R. James’s ghost stories

I didn’t expect to spend so much of Christmas 2021 rereading M.R. James ghost stories. However, like millions of other viewers on Christmas Eve my family watched Mark Gatiss’s adaptation of James’s The Mezzotint. It was so different from the story I remembered that on Christmas morning I reread the original – and this turned out to be such an instructive exercise that I spent several days dipping into the best of the stories yet again.

What is it that gives M.R. James’s stories their unique flavour? There is the background of ancient universities and libraries, the wind-scoured winter coasts of Suffolk and Norfolk, of deserted country churches and decaying country houses; the gas-lit streets of Victorian and Edwardian London, and the (entirely male) world of public schools, antiquarian research and bibliophily.

They are structurally interesting too. A significant proportion of them have a first-person narrator who is telling the story to colleagues in his club, his college ‘set’ or some other equally male setting – precisely as James himself did during the years when he read each new story as a Christmas or New Year treat for students at King’s College, Cambridge. (In some of the later stories he toys with this convention a little, breaking the fourth wall, as it were. In A Neighbour’s Landmark, for instance, the narrator is interrupted by a listener who says: “You begin in a deeply Victorian manner.” The narrator replies, waspishly, “I am a Victorian by birth and education…the Victorian tree may not unreasonably be expected to bear Victorian fruit.” This was probably about as close to modernism as MR James ever allowed himself to venture.)

Now I don’t for a moment think that screen adaptations have to be ‘pure’. Mark Gatiss’s and Stephen Moffat’s reinvention of the Sherlock Holmes short stories for the TV series was far from pure and yet was a genuine triumph, both enjoyable and exhilarating in the way it reshaped and expanded the Holmes canon. Sadly, this same trick wasn’t pulled off with The Mezzotint.

But this particular adaptation achieved something else. It made me reconsider the very particular merits of the stories themselves and the sometimes deceptively simple characteristics that give them their very special atmosphere.

It made me realise, for example, that generally speaking M.R. James doesn’t stoop to ‘magical’ devices. A burned engraving doesn’t ‘rematerialise’; creatures don’t step out of pictures and in through unguarded windows. His stories are driven by narrative and evocation; they hinge on atmosphere and descriptive writing; their terror is often primarily in the mind. Very rarely is there a clear, unequivocal conclusion: James’s narrators typically leave their listeners to make what they will of what they have heard. And scholarship and study are rarely absent – they are, after all, the ghost stories of an antiquary.

And as I reread story after story I also began to understand a simple truth that I had allowed to escape me. These are stories that can be returned to time and time again with undiminished enjoyment because, of their type, they are simply the best. And winter is the best time to read them

Alun Severn

January 2022

M.R. James elsewhere on Letterpress

Casting the Runes by M.R. James