Inspiring Older Readers

posted on 25 Nov 2021

posted on 25 Nov 2021

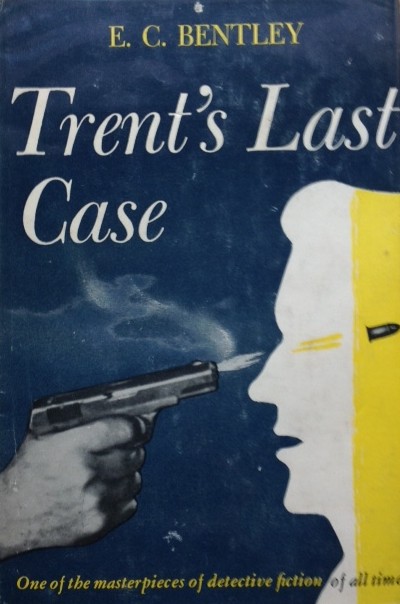

Trent’s Last Case by E.C. Bentley

Amongst aficionados of crime writing’s Golden Age, Trent’s Last Case by Eric Clerihew Bentley has something of legendary status. Bentley (1875 – 1956) was a minor novelist and inventor of the ‘clerihew’ poetic form that the Britannica dictionary defines as:

“a light verse quatrain in lines usually of varying length, rhyming aabb, and usually dealing with a person named in the initial rhyme.”

But in terms of novel writing, Trent’s Last Case is by some distance his biggest contribution to literary history.

From its publication in 1913 it has garnered the sort of critical appreciation that its Wikipedia entry describes in this way:

“G. K. Chesterton, author of the Father Brown mysteries, felt that this novel was "The finest detective story of modern times". (Bentley and Chesterton were close personal friends, and Bentley dedicated the book to Chesterton.) Agatha Christie called Trent's Last Case "One of the three best detective stories ever written". Dorothy Sayers wrote that "It is the one detective story of the present century which I am certain will go down to posterity as a classic. It is a masterpiece." Literary critic Jacques Barzun included it in his top ten mystery novels.”

In many ways, the case our amiable amateur detective, Philip Trent ( an artist and freelance journalist by profession) is hoping to solve looks to have all the mainstream features of classic detective fiction. When unscrupulous US industrialist, Sigsbee Manderson is found shot dead in the grounds of his English house, Trent, who already has a minor reputation for solving difficult crimes is invited by Manderson’s newly widowed wife to help with the investigation. The grieving wife is strikingly beautiful and has recently become emotionally estranged from her husband ; there are two male personal assistants and a handful of staff who may well be suspects. Equally, there’s an excellent chance that this was a ‘hit’ perpetrated by members of the trade unions that the industrialist is constantly fighting back in the States.

What makes this story different however is that Bentley is clearly – and rather affectionately – sending up the whole detective genre. Most obviously, he’s playing with the whole idea of the infallible private investigator who pieces together the clues, dismisses the unlikely red herrings and eventually draws back the curtain on the solution, unmasking the killer who thought they had covered all their tracks. Bentley takes us and Trent through all these steps – only to arrive in this case at the wrong answer. In fact, although Trent has correctly pieced together two-thirds of the puzzle, he needs the key suspect and the person who fired the deadly shot to explain to us exactly what happened.

And, in something of a departure from the usual plot development of the murder mystery, there is also a blossoming romance story involving Trent and the murdered man’s wife that runs through the book.

At the conclusion of all his misunderstandings and romantic entanglement, Trent’s analysis is this:

“…’I am cured. I will never touch a crime mystery again. The Manderson affair shall be Philip Trent’s last case. His high-blown pride at length breaks under him…I could have borne everything but that last revelation of the impotence of human reason.’”

So Trent’s first published case becomes his last case (although public pressure lured Bentley to bring Trent back again later but much less successfully).

There have been plenty of paperback editions that can be found very cheaply but if you’d like a first edition hardback for your collection, you’ll struggle to find one that doesn’t cost you several hundred pounds – and first editions with dust jackets are as rare as hen’s teeth.

Terry Potter

November 2021