Inspiring Older Readers

posted on 22 Sep 2019

posted on 22 Sep 2019

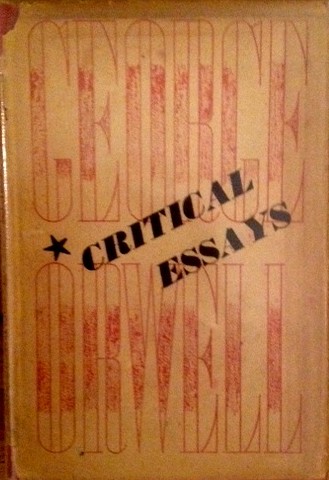

Critical Essays by George Orwell

It’s not a revolutionary statement to say that the very best of Orwell’s writing is to be found not in his novels but in his essays and journalism. These collections, as they were originally printed, are the ideal introduction to his work and will do more to explain why so many of us are bewitched by his writing than numerous readings of even his best novels. They are slim (less than 200 pages), varied in content and demonstrate just how broad Orwell’s interests were. And, to their inestimable benefit, the essays don’t get lost amid the multiplicity of content to be found in the (albeit admirable) collected essays and journalism.

The 1946 publication, Critical Essays, is probably my absolute favourite collection and I return to it frequently. It contains ten shortish essays and takes in literary criticism, contemporary politics, political theory, art and popular culture. Whether you agree with Orwell or not in his assessments, he never outstays his welcome and his willingness to give a subject like comic postcards a serious and thoughtful viewing was probably unparalleled at that time. But that’s not to suggest he treats all his topics in a po-faced way because he’s actually often hilarious – his dissection of Boys’ Weeklies makes me weep with laughter precisely because he doesn’t write it to be comical. He starts by examining the tradition of schoolboy comics – The Gem and The Magnet - that continued promoting a version of an ideal social class structure which remained unchanged from the high days of Edwardian England. The emergence of comics such as Wizard, Hotspur and Lion updated the fantasy of the model British hero – a hero whose mastery of the foreigner and disregard for personal safety was always from the realm of fantasy:

“Merely looking at the cover illustrations of the papers I have on the table in front of me, here are some of the things I see. On one a cowboy is clinging by his toes to the wing of an aeroplane in mid-air and shooting down another aeroplane with his revolver. On another a Chinese is swimming for his life down a sewer with a swarm of ravenous-looking rats swimming after him….On another a man in an airman’s costume is fighting barehanded against a rat somewhat larger than a donkey. On another a nearly naked man of terrific muscular development has just seized a lion by the tail and flung it thirty yards….”

But his real focus and concern is for the incursion of what he calls ‘Yank Mags’ into the market. These he claims are especially concerning because they introduce realistic – even sadistic – violence to the British reader for the first time.

What he rightly identifies is the fact that comics of that period inculcated hidden political messages – that they are written from a specific ideological position and that position was right wing and even authoritarian or fascist. So why in that case has the left never been able to pull off the same trick and make a progressive political position the moving spirit behind popular comics? Interestingly enough he has no answer to this conundrum, he just knows it’s an important question.

His lead essay on Charles Dickens which seeks to establish that author's credentials as a genuinely radical but not revolutionary author is an absolute must for anyone seeking a lively, sympathetic introduction that doesn’t get too bogged down in Dickensian iconography. The collection is bookended by a rather touching defence of the naïve and rather silly behaviour of P.G. Wodehouse during the war - a defence that would have been a pretty brave stance to take in the post-war atmosphere of Britain in 1946.

You’ll also find another delightfully droll essay about the comic postcard artist Donald McGill and what his popularity says about how the tradition of popular street caricature and satire had dwindled and softened until political comment became smutty inuendo embodied in these visual 'Carry On'-style cards. And, as if to prove his ability to come at topics from a lateral position there’s a combative and vigorous defence of the work of Kipling, defending the writer from the accusation of Fascist sympathies or old colonial Imperialism. I personally haven’t read enough of Kipling to judge whether the defence adds up to anything but it’s a bravado performance and the first time I came across Orwell’s brilliant notion of the ‘good-bad’ book, poem or author.

A number of these essays were written before or during the war and only slightly revised for publication in 1946 and in them you really do get both barrels of Orwell at the peak of his Orwellness. He’s a compelling champion if he’s on your side but (as Salvador Dali might have discovered if he’d read the essay about him) if he takes against you, you really don’t want to be in the cross-hairs.

Terry Potter

September 2019