Inspiring Older Readers

posted on 14 Sep 2016

posted on 14 Sep 2016

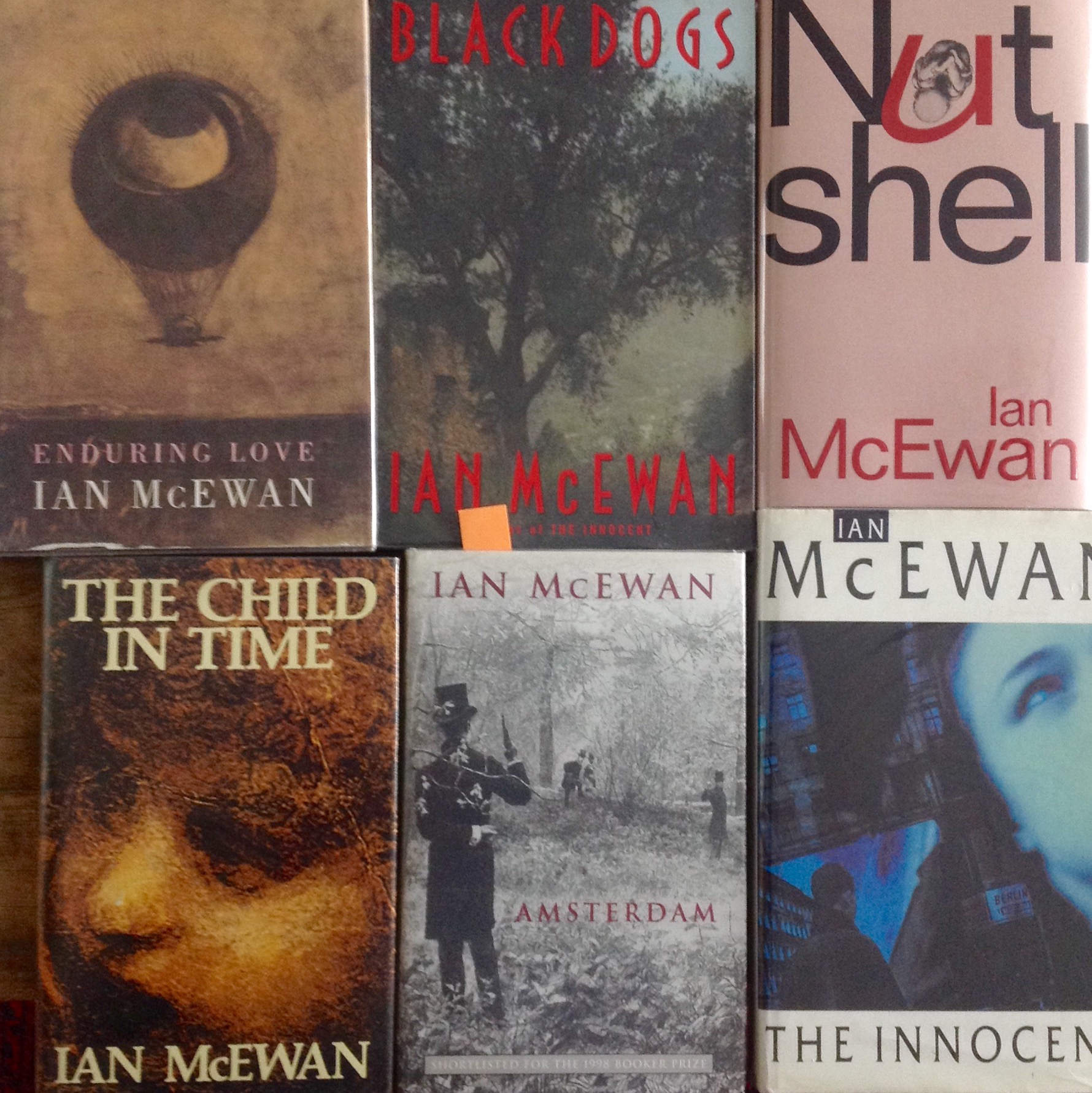

Rereading Ian McEwan

It is astonishing to think that Ian McEwan has now been publishing for five decades. I bought almost all of his novels as they came out, but from 2005, starting with Saturday, continuing with Chesil Beach, and then Solar, each seemed more gravely flawed than the last and I stopped reading him.

The problem as I saw it was that his novels had become stagey and overblown and resolutely upper-middle class. If working class characters intruded at all they did so only as a form of lumpen, menacing threat, more an eruption of subconscious fears than actual characters, capable of triumphing because unhindered by middle class gentility or conscience. And despite McEwan often being acclaimed as a great state-of-the-nation novelist, the world he depicted seemed increasingly old-fashioned. Everything, even the contemporary, seemed lifted from a dusty box marked “literary settings”. Saturday seemed to combine all these faults in one book and I still think it’s a preposterous novel.

But suddenly, perhaps because of all the recent media coverage of his latest book, Nutshell, I felt I wanted to rediscover what it was that had made him seem such a vital, unignorable novelist throughout the late-1980s and 90s, and I reread Amsterdam, The Innocent, Black Dogs and The Child in Time.

Amsterdam still seems only partly-formed, an idea that perhaps even McEwan lost interest in before the end. The mutual murder of its two curiously wooden upper-crust central characters seems no great loss to anyone – but the book has some marvellously insightful writing about music.

The Innocent begins as an apparently conventional espionage novel, rooted in social and historical fact. It seems plausible that a relatively low-level telephone engineer might be recruited to an ambitious cold war plan to tap Soviet communication lines in divided mid-50s Berlin. Location and period detail are lovingly painted in. But from there it spirals out into extremes of gothic horror that require a genuinely strong stomach to read. I’m still not sure about the overall purpose or integrity of this novel. Whether it has a point beyond its own gripping technique is unclear.

Black Dogs, however, I thoroughly enjoyed, as I did when it first came out. It is far from free of McEwan’s tendency to grand guignol, but it tackles some big ideas – often from startling perspectives – and the characters are fully engaging. What it has to say about politics vs faith or mysticism seems to have new contemporary relevance, despite the novel being almost twenty-five years old.

The Child in Time, written at the height of Thatcherism, I was surprised to find a far more complex and politically outraged book than I remembered it to be. My memory of it had shrunk to the sense of (absurdly) personal outrage I remember feeling on first reading it: that a child’s abduction was used to manipulate the reader’s emotions. My reaction was coloured by the fact that my own daughter was roughly the age of the abducted girl. This blinded me to the rest of the book. I’m still not sure the novel works entirely, and at times it seems there are several other books struggling to climb out, so dense is it with ideas, so hot with emotion, so unflinchingly imagined.

From this rereading I think I began to understand something about McEwan’s techniques and his real concerns (there is a lot to be said for being able to read a clutch of novels one after the other rather than separated by years). First, he isn’t especially concerned with plausibility. What really interests him – and he says this himself – are ideas, and in pursuit of ideas he will willingly sacrifice plausibility. Indeed, characters, situations, sometimes entire plot-lines often seem constructed solely in order to enable an idea to be explored. There’s no doubt that this is a weakness, but it isn’t quite as straightforward or as simple a weakness as I once imagined.

Second, he is a great prose stylist – but more than this, his prose is studded with darkly glittering insights that will make you wince with their accuracy. He has a sort of ruthless control and surgical sureness of touch.

Third, he is capable as few other contemporary novelists are of combining the personal and the political, the public and the private. His audacious leaps of imagination can make you gasp. Yes, he can be infuriating, but also thrilling, deeply intelligent, funny and humane.

But what this exercise in rereading has most taught me is that McEwan’s novels provoke and intrigue and at times outrage me much as I remember them doing over thirty years ago. He has grown into our 21st century Graham Greene: fertile, dismayingly inventive, obdurate (at times), and punishingly dedicated to the form he has made his own. And it turns out that I do feel compelled to keep reading. Do you?

Alun Severn

September 2016