Inspiring Older Readers

posted on 01 Dec 2015

posted on 01 Dec 2015

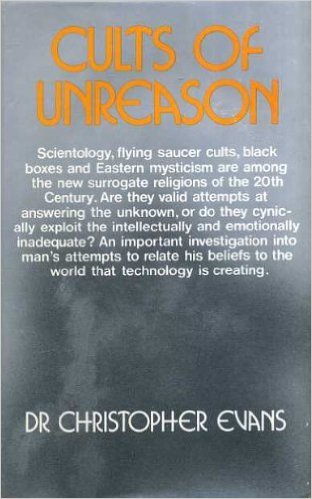

Cults of Unreason by Christopher Evans

There are some books I return to on a regular basis and which I don’t feel I have to read from cover to cover. Christopher Evan’s 1973 gem, Cults of Unreason, is one of those for me. The book is an exposé of the barmier end of the alternative belief spectrum – Scientology, UFOs, Eastern mystics, Atlantis and the like – written with no attempt to hide his amused bewilderment and wide-eyed incredulity.

Evans is a computer scientist and experimental psychologist who understands in detail the bogus claims made by pseudo-sciences like Dianetics or UFOlogy. However, rather than get angry or disgusted by their attempts to eye-wash the public, he responds with humour and ridicule and with a grace that is totally disarming.

I stumbled on this book entirely by accident in the mid-70s when it found its way into a remainder bin in Woolworths (looking back at that I’m really puzzled as to how it ended up there!) and I’ve cherished it ever since. This is a book that makes me laugh out loud but the detail that is rib-achingly amusing is also important and revealing and tells us a lot about the way in which charlatans operate. The dissection of L.Ron Hubbard and his theories of Scientology is truly magnificent, as are the descriptions of the works of George Adamski whose UFO drivel paved the way for Erich Von Daniken who made a fortune out of his classic, Chariot of the Gods.

However, by some distance, the choice chapter is the one which uncovers the story behind the early 70s cult phenomenon, T. Lobsang Rampa – he of the famous ‘third eye’. Rampa claimed to be a Tibetan mystic who had learned the secret of how to open the ‘energy centre’ of the brain that would allow us access to once known but long forgotten secret knowledge and powers. The Hippies of the late Sixties found themselves unnecessarily excited by the idea of a ‘third eye’ and got into some very questionable practices – including physically trepanning themselves in order to open themselves to the wonders of the universe.

Anyway, as Evans reveals, Rampa was a fraud. But it’s fair to say he was a pretty quick thinking and entertaining fraud. He was in fact Cyril Henry Hoskins, a British plumber who had, if I recall correctly, never left these shores let alone practiced as a yogic master in Tibet. Hoskins’ defence when exposed was nothing if not creative: yes, his physical body had never left the UK but is astral body had swapped with Lobsang Rampa’s at the moment of the latter’s death.

For sceptics and those who simply dislike snake-oil salesmen this book is an absolute must. The way Evans approaches his job is exemplary and with unfailing good humour. It could be argued that what he uncovers is no more than the equivalent of shooting fish in a barrel but that would be to forget the extraordinary influence many of these ideas had on a generation of people desperate to believe that the world has more to offer than what they were experiencing in their everyday lives. The fact that Scientology still has its high profile followers and that belief in UFO abduction is higher now than at any time in history tells us about the way this need to believe in something still bites deeply into the human psyche. We may have swapped some of the beliefs but we have simply replaced them with others no less incredible – how is it possible, it’s worth contemplating, that complementary or holistic medicine isn’t simply laughed out of existence or that ‘intelligent’ or ‘healing’ rocks and gems aren’t seen as the tripe they patently are?

Evans not only exposes absurd beliefs he makes us question why the human race is drawn to these stories and to ask us to consider what is missing from our lives that we fill the gap with fantasy.

Terry Potter

December 2015