Inspiring Young Readers

posted on 29 Dec 2019

posted on 29 Dec 2019

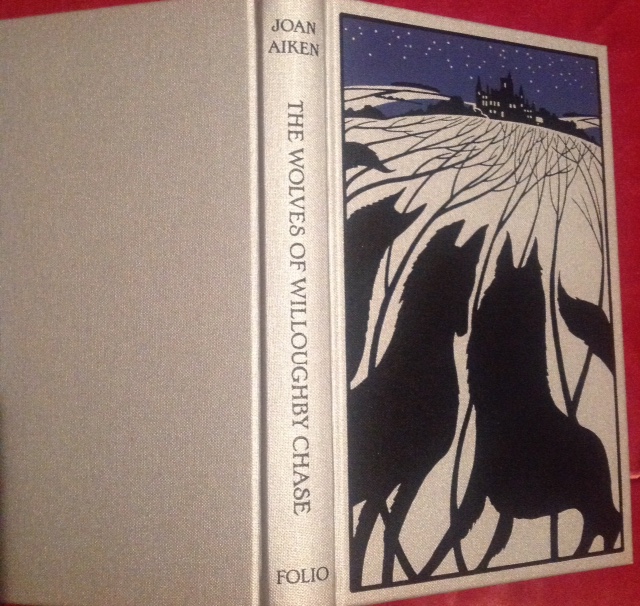

The Wolves of Willoughby Chase by Joan Aiken

The Wolves of Willoughby Chase is one of those ‘classic’ children’s novels that I never got around to reading until now. You might think picking it up for the first time in my sixties is a bit perverse but as Katherine Rundell points out in her superb essay 'Why you should read children’s books, even though you are so old and wise' (which I reviewed here), there’s plenty for an old stick like me to get from these classics. In fact, by coincidence, Katherine Rundell provides the introduction to the Folio Society edition that I purchased and her assessments of the book provide a perfect way into this book.

Set, as Rundell points out, ‘in an 1832 that never was’, this is in many ways the archetypal children’s adventure story of vulnerable but resourceful children in peril from ill-intentioned, greedy and even sadistic adults. It’s also a book that uses the external environment – wintery panoramas, forests full of ravening wolves – to mirror the internal landscapes of the characters and the dilemmas they face.

Condensed, the story doesn’t appear to amount to much that goes beyond the melodramatic cliché. When orphan Sylvia is sent to live with her kind, wealthy aunt and uncle they almost immediately decide to leave on an extended trip for the benefit of the aunt’s health, leaving Sylvia and her much more assertive cousin Bonnie in the care of their (obviously conniving) governess, Miss Slighcarp. This wicked governess soon shows her true colours by immediately making the young girls’ lives a misery. When Bonnie’s parents are reported dead in a shipwreck, Miss Slighcarp fires the household staff and sends the two cousins away to an orphanage. Together, with the help of the remaining adults and a young man who lives wild on the estate, Bonnie and Sylvia must escape and try to reclaim their home.

But summary of this kind really doesn’t capture the essence of the book. There is peril stalking almost every page and this is symbolised by the constant threat of the wild wolves that seem to be lurking in wait for the chance to pounce. And, of course, the ‘wolves’ that stalk Willoughby Chase aren’t just of the lupine variety – they take human form too in the shape of Miss Slighcarp and her sidekicks.

Aiken herself acknowledges her debt to Dickens in the way the book is structured and constructed:

“I think I got the idea for writing melodrama for boys and girls because when I was young, I had a great deal of Dickens read aloud to me. Of course, he is the prime example of this kind of melodrama. I think this had a very strong influence on my writing. The historical period of The Wolves of Willoughby Chase and the others is imaginary, although the trappings are all fairly genuine English nineteenth-century ones. This again, I think, was heavily influenced by Dickens. . . . The names of my characters have a strong connection with Dickens. Miss Slighcarp and Mr. Gripe, for example–this is the kind of name Dickens uses a great deal. A lot of my names, in fact, I tend to think of in dreams. I just leave the business to my subconscious, and it produces some fine names.”

The prose though is pure Aiken in that it rattles along barely giving you space to breath more easily. She also likes to give the reader an unexpected and sometimes unadorned shock – a wolf leaps through a train window and is dispatched by the use of broken glass, children are starved and locked in cellars, a ship is deliberately sunk for financial gain – which remind the reader that the world she has created is full of potential cruelty as well as kindness and decency. As with all of these classic adventure stories we see children embroiled in the never-ending battle between good and evil and, as the genre demands, it is good that must win out in the end. The wolves must be banished, or at least kept at bay, and order and decency must be allowed to re-establish itself.

“At the heart of The Wolves of Willoughby Chase there is hope, and goodness, and a desire to push forward its readers to build a better, bolder version of the world.”

Katherine Rundell concludes her introduction with this summation and it seems an appropriate way to recommend the book to readers of all ages. The Folio Society edition has the benefit of exclusive illustrations by Bill Bragg and is a whole lot cheaper that trying to get hold of a first edition. There are also plenty of paperback alternatives that won’t cost you much.

Terry Potter

December 2019