Inspiring Older Readers

posted on 08 May 2023

posted on 08 May 2023

Brave New World by Aldous Huxley

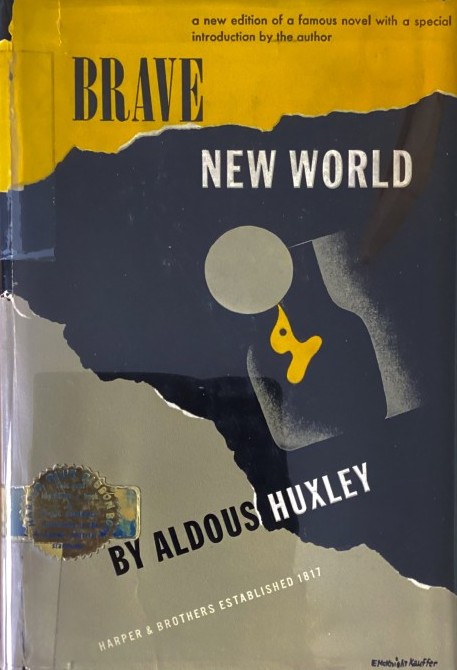

Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World and George Orwell’s 1984 must be the two so-called ‘dystopian’ novels that most people would immediately name if asked to produce a list of these books. It may be that Margaret Atwood’s Handmaid’s Tale is getting close to challenging their primacy but I still think it’s not quite there yet. It’s been a while since I last read Brave New World and having found a lovely 1946 American edition of the book with a jacket designed by the legendary designer E. McKnight Kauffer, I thought this was a good moment to see just how I felt about it all these years on.

There is a tendency in popular discourse to see dystopian novels as forecasts or predictions of the future and this, in turn, leads to some pointless speculation about what the author got wrong or what they missed seeing coming down the tracks. I’ve believed for a long time now that these books are in fact best read as critiques of the social, political and cultural concerns of their day. They retain their relevance for today only if they contain some bigger universal truths that can be translated into today’s environment and have significance for a contemporary reader. This I think is especially true of Brave New World.

First published in 1932, the society Huxley conjures-up in his novel is shaped around the concerns of that time – eugenics, social class, drug experimentation, the growth of commercialism and acquisitive capitalism. This has led a number of commentators to describe the Huxley future vision as ‘soft’ totalitarianism – an orthodoxy based on state paternalism expressed through the gratification of need and want. In this society, that has installed Henry Ford as a god, human reproduction has been supplanted by a laboratory process that pre-determines the social status of the embryo. It’s a world without friction or questioning and where hedonism is always the key goal. And to ensure this is the case, the sexual mores of the day have been reversed and physical intimacy is axiomatic with anyone you choose and there is an endless supply of ‘soma’ – a drug that guarantees bliss.

But occasionally the process of producing children who are constantly conditioned by the state slogans that underpin their conformity still produces an individual who has an inkling that there should be something more to life, something more elemental. Bernard Marx is one such ‘misfit’: but at least he’s an alpha – one of the top members of society and privileged to be able to do things others can’t. Others recognise him as a bit of an outsider but his status guarantees that he can still be found attractive by the ‘pneumatic’ Lenina, who he convinces to accompany him to a ‘savage reservation’. Modelled on the US native-American reservations, these are places where people still live by the old codes and where alphas like Bernard can sometimes visit on the pretext of research.

Here the two visitors discover that a young woman from their world had been left stranded there some years previously (by Bernard’s boss) and now lives – with difficulty - by their codes. She has had a child, John, who has now grown into a young man and has learned to read and write almost exclusively from an old copy of the complete works of Shakespeare.

Bernard contrives a way to bring these two back from the reservation and introduce them to the modern world – with predictably disastrous results.

For Huxley, both the options – the hedonistic totalitarian and the ‘free’ savage world – are versions of an insane society it’s impossible to live in. In a later 1946 preface to a new edition of the novel, Huxley claims that this, he now believes, is a false dichotomy and that a ‘third way’ is possible – one based on Eastern mysticism. But this itself seems a rather vague and unconvincing set of concepts.

The idea that Huxley’s novel represents a sort of soft totalitarianism is usually postulated by comparison with the later 1984, where Orwell’s state totalitarianism is enforced by brutality, force and cruelty. It could be argued with some fairness that both of these versions of state control exist now in various forms and that neither version need be seen as the ‘correct’ interpretation. Just as Huxley’s novel reflects his own social concerns, Orwell’s are those of the post-Second World War world.

For me, Orwell’s is the better novel – not because of the central conceit but because it is just better written. Huxley’s future world is all about sensory experience – sights, smells, feelings – but there is really very little ‘rounding-out’ of character or background. This is something I think Margret Atwood alludes to in her article about the book in The Guardian in 2007:

“…Brave New World - gulped down whole - achieves an effect not unlike a controlled hallucination. All is surface; there is no depth.”

Huxley was a prolific novelist but he was also hugely interested in philosophy, religion and what we'd now think of as popular science. He experimented with drugs well ahead of those who came along in the later 1950s and 1960s and all of these are important elements in the recipe he used to construct Brave New World. I think it is this rather heady mix of subjects that has consistently found an audience for the book with every subsequent generation and kept Huxley as an author who can be cast as a pioneer of the alternative and cultish. It is certainly a book with plenty of faults and frayed edges but it is also a book that raises some interesting questions for readers in the 21st century.

Paper and hardback editions are easily available at a range of prices starting at about £5.

Terry Potter

May 2023