Inspiring Older Readers

posted on 22 Feb 2021

posted on 22 Feb 2021

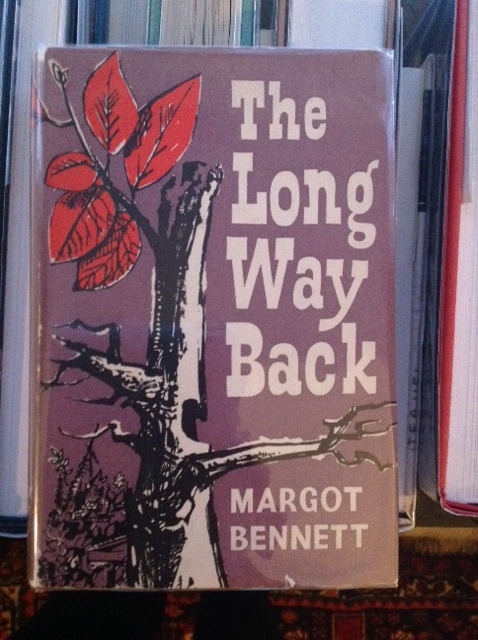

The Long Way Back by Margot Bennett

In October of last year I wrote a slightly snivelling article about just how impossible it has been to find a copy of Margot Bennett’s The Long Way Back. The fact that I couldn’t find a copy to buy made it the book I just had to have – and all that I’d read about it seemed to add to that glow of desirability that I felt surrounded it. It wasn’t just an issue of its rarity – what reviews there were made it sound like a seriously unusual and thought-provoking read. In that previously mentioned article I outlined why I was so desperate to get hold of it:

‘The latest book to tease me in this fashion is Margot Bennett’s The Long Way Back. Originally published in 1954, this is one of Bennett’s occasional flirtations with ‘science fiction’ – or, as I would prefer – ‘future fiction’ and deals with a set of remarkably provocative ideas. Sonia Mullett on the Holdfast website provides a tempting summation of the plot:

“In The Long Way Back, Bennett presents a dystopian post nuclear-war future. The global North has long since been laid to waste and now history is poised to repeat itself as a nuclear-armed Africa competes, Cold War-style, with South America. A team of African scientists is dispatched to the little-known British Isles to seek out exploitable resources – a case of colonial history in reverse. It soon becomes evident that, if Britain proves rich in coal and other assets, the new imperialists will show about as much consideration to the island’s indigenous population (stuck in a stultifying stone-age of wild killer dogs, mutant ants and homicidal cavemen) as they do to the poverty stricken white Boers back home.”

Colonialism and sexual politics also emerge as key themes according to Mullett and, given the remarkably contemporary nature of the themes she is tackling, I can only agree with her when she writes “ it’s still a surprise to discover that most of her books, though inventive and respected by critics, are out of print.”’

So there’s no need for me to recap on the central plot and themes. What I can say now is that, finally, I did indeed find a copy and now I’ve been able to sit down and gobble it up.

What you might be interested to find out is whether the battle to find myself a copy and the not-insubstantial price I had to pay for it was worth all the effort?

Well, maybe inevitably and possibly infuriatingly, the answer is yes and no. It’s not a lost masterpiece in literary terms – some of the characterisation and rather sloppy use of stereotypes works against it – but it is a novel full of big ideas. The inversion of the colonial story of exploitation and what might be thought of as ‘exotic’ raises plenty of questions about imperialism and empire for a novel written in the 1950s where such questions were not the regular stuff of popular fiction.

But I was disappointed to find a woman novelist creating such a cardboard central female character as Valya – the supposed leader of the expedition. She comes across as a character whose power is constantly undermined by irrational sexual emotion and an unstable sense of self. We are forced to conclude her mismanagement of the project is as much about her gender as about her capabilities. By contrast with the male character through whose eyes the whole story is mediated, the female lead becomes a stereotypically hysterical and unreliable ‘little woman’. Disappointing.

But it’s fair to say that the book as a whole isn’t as disappointing as that particular aspect of the story – in fact it’s quite thrilling to find another forgotten science fiction story that tries to transcend its genre. The book certainly doesn’t deserve to have disappeared and I’m at a loss to understand why this remains out of print – it does, in my view, bear a decent comparison with the likes of Joanna Russ who has a growing cult reputation in the field of feminist speculative fiction.

So I’m glad I persisted and I don’t regret the expense. But I also have to say I wouldn’t be surprised if your assessment of the novel was quite different.

Terry Potter

February 2021