Inspiring Older Readers

posted on 26 Nov 2019

posted on 26 Nov 2019

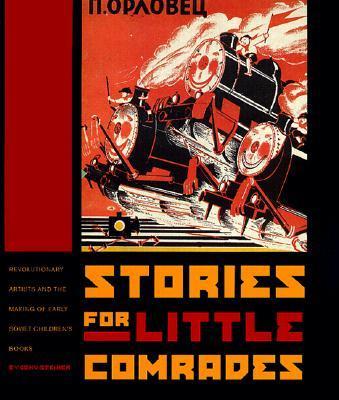

Stories For Little Comrades by Evgeny Steiner

At a time when politics in one form or another seems inescapable, the idea that we might at least find some temporary respite in the world of children’s books is an alluring one. Worlds of forever summers, fantasy islands or anthropomorphic farmyards might seem to offer a potential haven but Evgeny Steiner’s academically rigorous ‘Stories For Little Comrades’ will soon lay all these fond hopes to rest.

What this beautifully produced publication from 1999 does is to dig down into the way the Soviet Union used the art of the children’s book as a crucial tool in their propaganda war. And while he argues that there were very specific circumstances around the politics of the Soviet Union and the needs and aspirations of the illustrator artists who fulfilled the demand for ‘progressive’ children’s literature, this book can in fact be read as a kind of case study for the way this genre has been used universally by dominant political hierarchies to bolster and disseminate the the dominant political values they seek to promote to an upcoming generation.

Steiner’s approach might feel a bit off-putting at first – it is an academic study and I’m not always sure it’s terribly well served by the translation (although, not speaking Russian myself this is just a guess) and you do have to persist and get into the style and use of language. That does pay off because it becomes much more amenable the further in you get. There is a distinct danger you’ll abandon this at the Introduction stage but don’t; try to get past that and into the body of the work.

The author relies on going back to primary sources – the books themselves – and this is a sound approach. He had access to Russian picture books from the Russian State Library, private collections and publishers’ archives and the result is that he’s able to see each publication in the round and as physical objects. It probably hardly needs to be said that there are books featured and analysed here that have never made their way in any accessible form to the West until pretty recently and the bounty of the illustration in this book make it worth having just for the examples he reproduces and turn the text into a bonus. Perhaps the one downside is that there are too many black and white reproductions when more colour would have helped.

Although it can feel dense at times, I think Steiner’s central premise is not too difficult to get hold of and in the end he provides a good compelling narrative. Essentially he argues that for avant-garde artists of the 1920s, children’s book illustration offered a chance to reach a mass audience of ‘unformed, malleable young people’ and that this ‘appealed to their commitment to an art manifesto based on the creation of a new kind of person for the revolutionary age’. They did, of course, also have to have a mind to the simple requirement to earn a crust in a way that didn’t bring them into conflict with the State or, at least, the censorship rules.

For those artists who we’ve come to know as The Constructivist school, who were by that time drawing attention in the West for their ‘brilliant creativity in using geometric designs, machine-age forms, and an architectural sense of space in their approach to the visual arts’ this was a chance for them to also develop their own manifesto and approach to art:

“Rejecting easel painting as a passé bourgeois preoccupation, they turned to designing and mythologizing objects of everyday use.”

Despite their eagerness to be seen as iconoclastic and anti-establishment, Steiner argues that the Constructivists were in fact ideological fellow-travellers with the dominant Communist Party and their commitment to the revolutionary utopia was no less ruthless.

I think this book is a must for scholars of children’s literature and for anyone interested in the cultural and artistic development of Soviet thought following the Revolution. It’s not necessarily relaxing or casual reading but it is stimulating if you’ve got the stickability to stay with it.

It’s not a cheap option – you’ll pay around £20 for a copy – but the production values of the book are high and the illustrations will knock you out.

Terry Potter

November 2019