Inspiring Older Readers

posted on 13 Feb 2019

posted on 13 Feb 2019

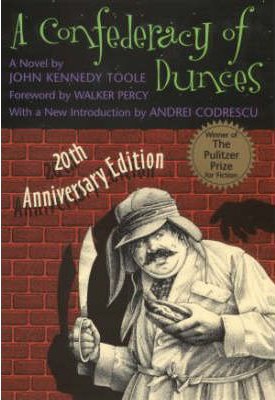

A Confederacy of Dunces by John Kennedy Toole

This is one of those novels that was destined to have a cult following – the extraordinary story of how it found its way into print alone guarantees that. Toole wrote the novel in the late 1960s but could not find anyone interested in publishing it – a situation that played a fairly major part in the author’s tragic and untimely suicide in 1969 at the age of just 31. The novel would never have seen the light of day had it not been for Toole’s mother, who found a copy in his effects and set about nagging the novelist, Walker Percy to read it. He resisted, she persisted. Eventually he gave in and was an instant convert to its cause – a fact he recalls in the book’s preface:

“..the lady was persistent, and it somehow came to pass that she stood in my office handing me the hefty manuscript. There was no getting out of it; only one hope remained—that I could read a few pages and that they would be bad enough for me, in good conscience, to read no farther. Usually I can do just that. Indeed the first paragraph often suffices. My only fear was that this one might not be bad enough, or might be just good enough, so that I would have to keep reading.

In this case I read on. And on. First with the sinking feeling that it was not bad enough to quit, then with a prickle of interest, then a growing excitement, and finally an incredulity: surely it was not possible that it was so good.”

So, in 1980 the book was first published and in 1981 it was awarded the Pulitzer Prize as well as being regularly cited as a significant late 20th century contribution to the canon of Southern American literature.

The book’s satirical intent is signalled in the title which is lifted from the master of literary satire, Jonathan Swift. But it is also a roister-doistering Picaresque comic romp where absurdity, grotesquery and sheer bad taste are shot through the narrative like a resort’s name through seaside rock.

This isn’t the sort of book where it’s possible to give a short and pithy synopsis of the action – so I’m not even going to try. The cast of characters move across the book as a gallery of oddities, social freaks and eccentrics and, as is the usual convention with the Picaresque tradition, character development and character building is not a feature of the writing. They are cartoons - much in the way that the those created later by Carl Hiaasen’s are and there are even shades of Elmore Leonard’s more disreputable cast of villains.

Toole also puts his central anti-hero, Ignatius Reilly, into a series of absurd settings that mirror the flamboyance of his characters. So we enter a sleazy stripper bar, a clothing company specialising in pants (trousers), a street hot-dog franchise and the world of the splendidly crazy policeman, Officer Mancuso.

But in truth none of this counts for anything much when set alongside the monumental central character of Reilly and whether you like this novel or not is going to hinge on just how much you take to him.

At the beginning of the novel we get this description of our ‘hero’:

“A green hunting cap squeezed the top of the fleshy balloon of a head. The green earflaps, full of large ears and uncut hair and the fine bristles that grew in the ears themselves, stuck out on either side like turn signals indicating two directions at once. Full, pursed lips protruded beneath the bushy black moustache and, at their corners, sank into little folds filled with disapproval and potato chip crumbs. In the shadow under the green visor of the cap Ignatius J. Reilly’s supercilious blue and yellow eyes looked down upon the other people waiting under the clock at the D.H. Holmes department store, studying the crowd of people for signs of bad taste in dress.”

He lives at home with his put-upon mother, bad mouths everything he associates with the ‘modern world’ and sees the worst of everyone in it. His views veer from unlikely liberality to an unhinged conservatism. There’s nothing about him to like except the thought rumbling away in the back of your head that maybe Ignatius J. Reilly is the everyman we sort of deserve. He is the crazy lens through which we see most clearly the fractured society we’ve created. There are those critics who argue that embodied in Reilly are all the facets of life and social attitudes that come together to make up the city of New Orleans – and I can see how that might be part of the intention here.

But, as I said earlier, you do have to go with him and ride the often unpleasant eddies of callous, bigoted, opinionated and self-centred bellowing that wash up in his wake. Sam Jordison writing in The Guardian in 2017 is more or less convinced of the significance of the novel despite the fact that:

“Ignatius J Reilly is, in some ways, an eerily accurate prototype of the internet troll: a man who tongue-lashes everyone and everything, rather than confront his own sense of inadequacy. He masturbates while thinking about dogs, then spends long hours inside frantically and angrily writing about “degeneracy” and “the awful spectacle of the Negroes moving upward into the middle class”.

This was a rereading for me after a gap of a couple of decades and I have to say that I loved it the first time around. However, this time I found that the longer the book went on, the more I became uncomfortably conscious that Reilly was an engagingly artful plot and narrative device rather than a three-dimensional character. My patience with the predictable farce that surrounds his every action and utterence was strictly limited and I often found it irritiating rather than amusing. It is, of course, a convention of the Picaresque novel that the main character should behave in ways that remain true to a fixed persona that seems ultimately impervious to life's ups and downs and which stays largely untouched or unmodified by experience. Ultimately, however, what worked in the context of an 18th century audience reading a book like The History of Tom Jones is somewhat harder to pull off successfully with a modern day audience that is now used to more sophisticated character development. In the same way as cinemagraphic characters like Mr. Hulot or Inpector Clouseau can tip over from amusing innocence and simplicity into being tiresome and two-dimensional, so Reilly and his activities stop being anarchic or satirical and become the actions of a cartoon cipher. The result is that I simply couldn't sustain the suspension of disbelief needed for me to enjoy the book for a second time.

There are, however, plenty of people out there who would disagree with me and I have a sympathy with those who now look at Trump’s America and find Toole’s novel has a startling new relevance. And maybe ultimately that’s the biggest barrier for me – I don’t live in America and this is, above all else, an American book.

Terry Potter

February 2019