Inspiring Older Readers

posted on 05 Aug 2018

posted on 05 Aug 2018

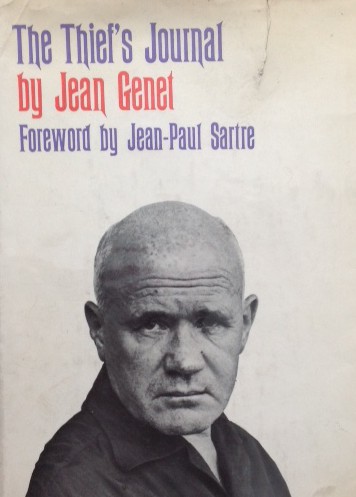

The Thief’s Journal by Jean Genet

In the introduction to the 1964 Grove Press first edition of Jean Genet’s The Thief’s Journal, Jean-Paul Sartre says that this is ‘the most beautiful (book) that Genet has written’. But he also has this to say:

“Genet sees himself everywhere; the dullest surfaces reflect his image; even in others he perceives himself, thereby bringing to light their deepest secrets….Here Genet speaks of Genet without intermediary….He does, to be sure, tell us everything. The truth, the whole truth and nothing but the truth…”

And while this is certainly the case, ‘the truth’ is not necessarily a historical or chronological truth but more a spiritual, ethical and moral truth – the world as filtered through the complex creature that is Genet. Which parts of this narrative are factual and which are fictional matters not a jot because they are all true in terms of the Genet universe.

The journal of the twenty-three year old Genet is a lyrical, philosophical and eroticised journey to the lower depths of European society between the world wars. He roams from France to Spain (especially Barcelona), across to Eastern Europe and back to Antwerp living in a sort of romanticised squalor, sustained by means of petty theft, scams of all kinds and prostitution. Everywhere he goes, everyone he meets and every situation he seeks out is evaluated for its homoerotic possibilities. At times he’s less a man and more a sentient, walking, calculating phallus.

He’s drawn to manly men who are themselves homosexual but whose status in this shabby underworld depends on them carrying the menace of a heterosexual gangster. As a result Genet himself is often subservient to these men and he ‘loves’ them without qualification and, as a result, he struggles to find his own identity until he is forced to travel alone.

The narrative is broadly linear and chronological but it’s quite hard to follow the path he takes because he drifts into episodes of philosophical and artistic speculation or he paints a vivid vignette of an episode of emotional or physical intensity. In these moments the truth of the detail is important to him. Spit, smells, lice and filth are painted in vivid detail but the honesty and visceral nature of the descriptions are not presented in the way someone like George Orwell described the tramping experience. Where Orwell is material and factual, unadorned, Genet is quite the opposite in his approach. His writing spangles the filth with a sort of lyricism that imbues the gutter with its own sense of majesty.

Genet says, more than once, that his aim is to be honest and to set out unadorned and truthful portraits of the people in this world but I think Sartre is right, it’s Genet that is always the subject of his writing. In holding up a mirror to this underworld, Genet is really holding up a mirror to himself. Everything and everyone is a reflection of him and his constantly present sexuality.

Two-thirds of the way through the book, Genet captures the essence of his enterprise:

“Betrayal, theft and homosexuality are the basic subjects of this book. There is a relationship between them which, though not always apparent, at least, it seems to me, recognises a kind of vascular exchange between my taste for betrayal and theft and my loves.”

How many of Genet’s encounters actually happened and how many are fantasy wish fulfilment is impossible to say but the prevalence of obliging policemen, coastguards and sailors seems to play suspiciously to what are now rather clichéd gay fantasy figures a la The Village People.

The journal isn’t presented as a confessional nor as a moral mea culpa – there are no apologies and no justifications. Genet is clear that this is a life he has chosen, that repeated periods of imprisonment are simply a matter of fact in this world and that the freedom of his (erotic) soul – his desire to love intensely – is the key to understanding his choices.

There are plenty of paperback editions of the book available – including a Penguin Modern Classic edition – which can be picked up for pennies.

Terry Potter

August 2018