Inspiring Older Readers

posted on 02 Apr 2018

posted on 02 Apr 2018

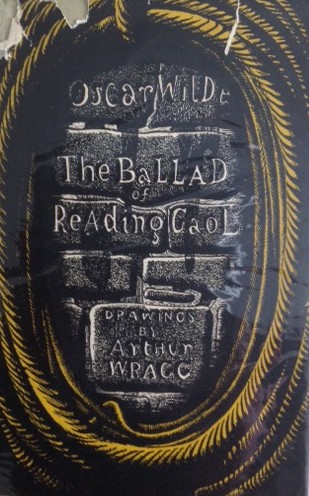

The Ballad of Reading Gaol by Oscar Wilde with drawings by Arthur Wragg

Arthur Wragg, Christian Socialist, pacifist, political campaigner and artist, provided the introduction to this copy of Wilde’s The Ballad of Reading Gaol as well as some stunning illustrations. Wragg believed this was Wilde’s most convincing and deepest piece of work:

"It is his masterpiece because it was almost the only time he allowed himself to express a deep and genuine emotion which he regarded as aesthetically destructive to a work of art. Yet his Ballad gives more, demands more and means more than anything else he wrote."

Wragg praises the poem for its compassion and for Wilde’s ability to go beyond a single, personal experience and make a much broader case for prison reform.

In this introduction, written in 1948, Wragg himself is unable to mention the nature of Wilde’s ‘crime’ – homosexuality was still something never uttered in decent company at this time and was, of course, illegal and could still result in imprisonment for anyone who confessed themselves to be ‘practicing’. Wragg’s own outrage at Wilde’s treatment doesn’t prevent him however from making quite clear where he stands on the issue:

"In punishing him for a ‘deviation’ for which he could not be blamed, his world squeezed this final masterpiece from him not because it intended to, but because it could not destroy that which he failed to destroy himself."

This is quite an explicit message from someone who was a militant Christian and something that showcases Wragg’s own compassionate nature.

I expect that most people will be familiar with Wilde’s Ballad, written at the very end of the 19th century, a year or so after his release from Reading gaol. At the time he was in exile in France and was, in many ways, a broken man. He died in 1900, just two years later.

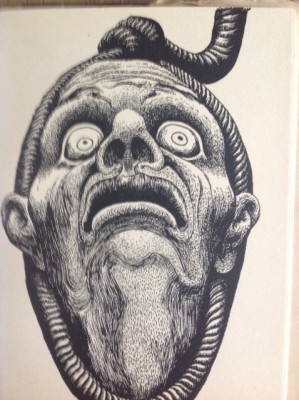

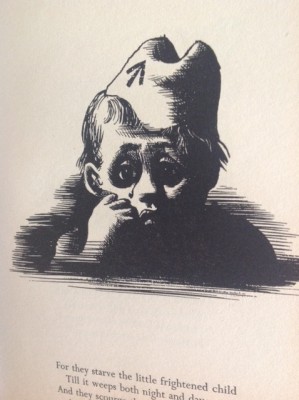

In the poem, Wilde had witnessed the execution of a young man convicted of murder and this incident led him to think about the impact of this event not just on him but on the other inmates. What makes the poem special is that he’s then able to broaden his thinking to consider how the inhumane treatment of the condemned man reflected on a ‘civilised’ society prepared to treat people in this way. Wilde’s understanding that prison brutalises more than it reforms turned out to be an extraordinary weapon for campaigners seeking prison reform.

Wilde contrasts the taking of this life with a society that calls itself ‘Christian’ and he sees that prison kills in more ways than one – he draws parallels between the execution of the body with the execution of the spirit. Wilde himself may not be there to be executed in the way the poor wretch he witnesses was but he still has had his own life ended in the brutality of the hard labour regime:

Yet each man kills the thing he loves

By each let this be heard.

Some do it with a bitter look,

Some with a flattering word.

The coward does it with a kiss,

The brave man with a sword!

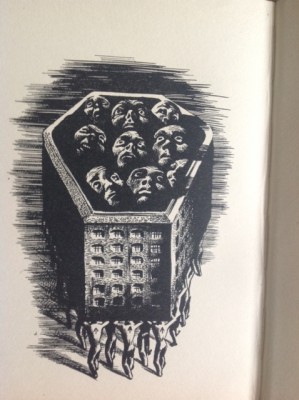

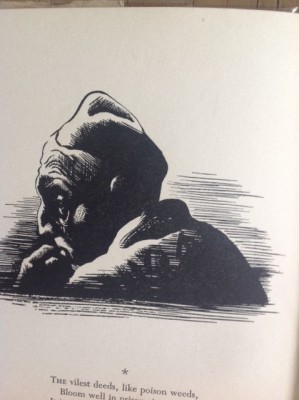

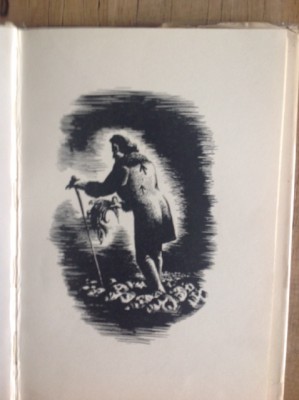

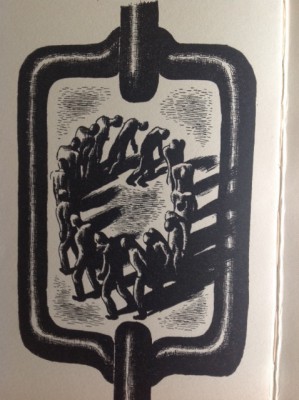

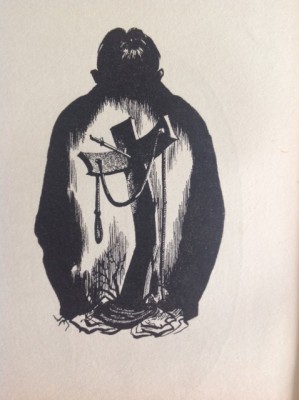

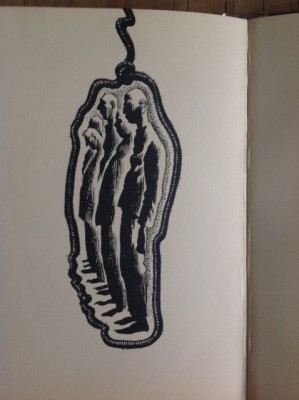

Arthur Wragg’s illustrations are bold and dramatic and very similar to his other publications that often dealt with social and political alienation, poverty and inequality. Wragg only drew for publication because he believed strongly that his work needed to be viewed and democratically available – he saw the fine art world as a plaything or investment opportunity for the rich.

Central to Wragg’s vision is the dramatic moment, very often rendered in close-up. He alternates these with more symbolic images that seek to capture an idea or even an ideology and which are framed within the page.

Published by The Castle Press in 1948, this has been out of print for some time – Wragg’s work now is, I think, quite unfashionable. You can find copies of the book on out-of-print websites for under £20 if you’d like to explore this in more detail.

Terry Potter

April 2018

( Click on any image below to view them in slide show format )