Inspiring Older Readers

posted on 10 Sep 2017

posted on 10 Sep 2017

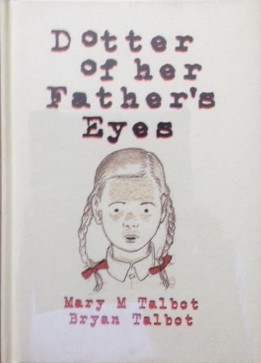

Dotter of her Father’s Eyes by Mary M. Talbot and illustrated by Bryan Talbot

I’m not, by temperament, a reader of graphic novels but the subject matter of this one and the extraordinary audacity of the project convinced me that I ought to take a look. I’m also aware that when it was released back in 2012 it garnered pretty much universal praise and was, I think, the first graphic novel to get a major book award nomination.

Mary Talbot is an academic of some standing with published work on language and discourse analysis – her reputation though is largely built on her critical investigation of teenage girls magazines and what she called the ‘synthetic sisterhood’. But what she investigates in this book is her childhood with her famous father, James S. Atherton who was a pioneering and significant James Joyce scholar and expert on Finnegan’s Wake. It’s fair to say it was something of a volcanic relationship and often a miserable one.

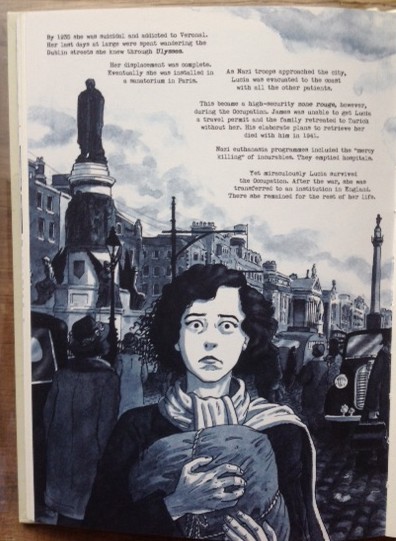

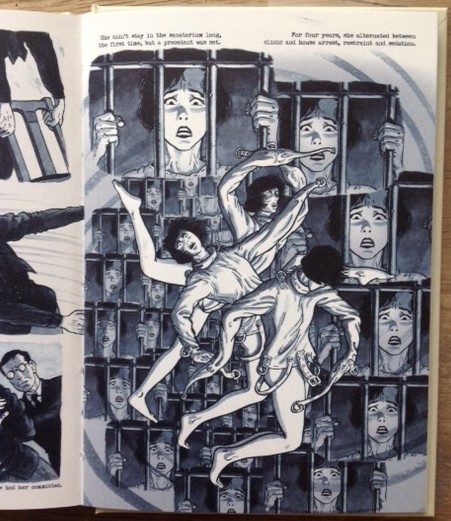

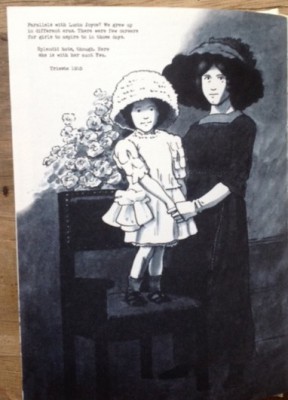

But what really lifts this memoir onto another level is the way Talbot intertwines her story with that of the relationship between James Joyce and his troubled daughter, Lucia. She clearly sees direct parallels between her life as the daughter of an unpredictable Joyce scholar and Lucia’s life as daughter of an equally unpredictable novelist. Her opening dedication makes this crystal clear:

Once upon a time

And long ago

A king and a queen

Had a daughter

Her name was

Marushka

Or Lucia

Or Lucy Maria

Or Mary

Although the two narratives are very different strands there are echoes across time that, thankfully, she doesn’t labour or make too obvious. We are allowed to make our own connections across the two stories and find the similarities for ourselves. Talbot’s father was an often violent and moody man who always put his work first and would tolerate no disruption of his space but was equally capable of moments of great love and tenderness. Joyce, by contrast, was a much more mild-mannered man, a dreamer who was all too often unaware or perhaps indifferent to the needs of a daughter whose mental health was always precarious. Both women had their lives shaped by talented fathers and we’re left to reach our own conclusions about how this all worked out.

Lucia’s life ended tragically but Mary’s took a different direction – so there’s nothing fatalistic or mechanistic about the narrative. But there is plenty here to think about in the father/daughter relationship and it’s a really fascinating way into an aspect of Joyce’s life that we don’t often get to see.

The success of any graphic novel does depend, of course, on the quality of the artwork that presents the story and Mary Talbot is fortunate to have a husband who is one of the premiere exponents of the adult graphic novel. Rachel Cooke reviewing the book in The Guardian has this to say about the inter-relationship between the two narratives and the artwork:

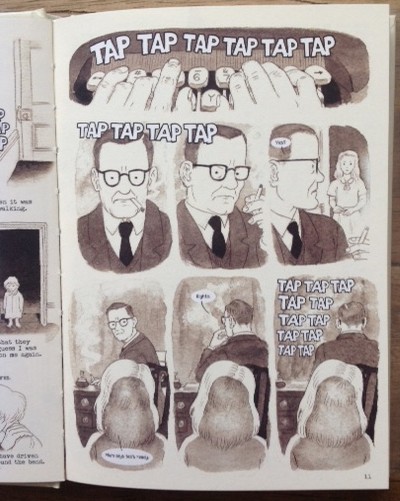

Mary M Talbot is married to the great Bryan Talbot (Alice in Sunderland, Grandville), and he has kindly provided for her some of the most beautiful and poignant drawings of his career: black and white for 30s Paris; sepia tones for postwar Britain; full colour for the present day. He and Mary met and married in 1970 – his drawing of their wedding day, all flares and innocence, will make you cry – and they have been together ever since (this is where the two narratives peel away from one another; unlike Lucia, Mary had a supporter to see her through).

Stories of abuse and neglect sound like a recipe for depression but actually the experience of reading this is not at all miserable. Talbot is ultimately a survivor, she could have gone down as Lucia did, but she didn’t – and this is almost the definition of resilience. You’ll finish reading this book and feel that you have, in some way, been lifted by two strong women.

Terry Potter

September 2017