Inspiring Older Readers

posted on 22 Aug 2017

posted on 22 Aug 2017

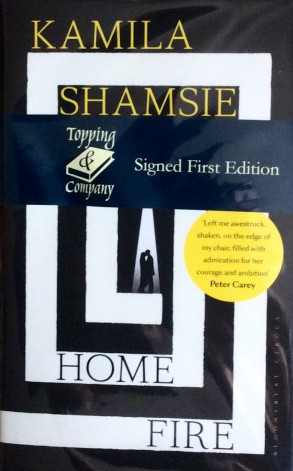

Home Fire by Kamila Shamsie

Kamila Shamsie is the author of several prizewinning novels, many of which explore aspects of identity, family and the complications of having a dual British/ Pakistani heritage. This powerful story continues these themes and is also described as ‘a contemporary reimagining of Sophocles’ Antigone’, a play originally written in 441BC.

The opening part of the book is set in a UK airport terminal where we meet Isma, a Pakistani born Londoner, who is on her way to Amherst, Massachusettes where she is hoping to begin a PHD course in sociology. The journey is not as easy as it might be because, as she fully expected, she has been selected for interrogation before boarding her plane because of her ethnic background. Although her younger sister, Aneeka has helped her to prepare acceptable answers to questions about her ‘Britishness’, the author gives us a vivid flavour of the tension and frustration that Isma experiences as she struggles to keep calm and polite in the face of suspicious officialdom. This effectively sets the scene for what is an on-going struggle for other British Asians who are expected to ‘prove’ their nationality in this particular story and also reflects the real world experience of many.

Isma has brought up her much younger twin siblings, Aneeka and Parvaiz, after the death of their mother when they were only twelve years old. Family life had always been difficult because their absentee father had been fighting for many years as a jihadi in Kashmir, Chechnya and Kosovo. His children know very little about him other than that he was arrested and imprisoned in Afghanistan and then apparently died during take- off on a plane going to Guantanamo. This close link with a terrorist has always been very problematic and one that the family has tried to keep secret for obvious reasons, having had little sympathy or support from their local Asian community. Although they wanted no part of his politics, Isma’s grandparents and mother had wanted confirmation of the circumstances of his death, but could find out no information from official channels. Many years earlier there was at last a glimmer of hope when the son of a family friend’s cousin became an MP, Karamat Lone. When the MP was approached for help in discovering more about lack of information, his disappointing response was ‘They’re better off without him’. Lone has been a very successful and outspoken politician who has recently been appointed as the Home Secretary, which is seen as a remarkable achievement for a man with his very ordinary Pakistani background. He is constantly under pressure to tread a line between being loyal to his traditional Pakistani Muslim roots and a more progressive cosmopolitan set of values.

Lone is significant to the story because he is the father of Eamonn, a young man who becomes a close friend to Isma whilst she is living in America and later becomes the lover of Aneeka back in England. You may already have guessed that this is a very complicated story with many interesting characters whose lives become more and more entwined. Aneeka and Eamonn’s short affair is intensely passionate but ultimately doomed because of the politics of both their fathers:

It didn’t matter if they were on this or that side of the political spectrum, or whether the fathers were absent or present, or if someone else had loved them better, loved them more: in the end they were always their fathers’ sons’.

But the most important and long lasting relationship in this novel is the one between the twin siblings. Aneeka has grown up to be a clever and confident law student who enjoys living a life that includes plenty of fun and boyfriends. Parvaiz is very different to his sister and, although he has many interests, he lacks direction and has become a young man who needs to feel proud of his father. When he becomes involved with a group of men who revere his father as ‘a great warrior’, he becomes drawn into the romance of freedom fighting as a way of both asserting and defining himself. He is used to being encouraged to feel ashamed of his father but is fascinated to hear all the stories about how he was charismatic and brave. Over some time he is encouraged to see his sisters as the enemy:

They want you to be in the house, doing their shopping and mowing the garden, so they’ve tried to keep you a boy, a child in need of a mother’.

Inevitably, Parvaiz is manipulated away from Isma and Aneeka and his other interests to become focussed on fighting for the Islamic cause, like his father. As I read about his changing personality and priorities, a process that is usually termed ‘radicalisation’, I realised how very attractive these stories must be to young men who need to feel important. Parvaiz is lured away from his sisters and willingly goes to fight in Syria which includes a brutal training regimen. After witnessing several atrocities, he realises that he cannot stomach the regime any longer and so wants to return home to England. Without spoiling the plot, this proves to be impossible despite Aneeka’s pleading on his behalf via Eamonn, as the Home Secretary is determined to stand firm on being seen to favour a potential terrorist.

And so the dreadful tragedy unfolds and, as in Antigone, the decomposing body of a young man is left unburied to be tended by a loyal sister in a determined challenge to the law as interpreted by a Government. I found the last part of the novel where Aneeka sits in stubborn vigil ‘out of her mind with grief’ over the body of Parvaiz was graphically described and extremely moving. This beautifully written haunting story has an extraordinary ending which took me completely by surprise. I suggest that you read it for yourself to find out what happens.

Karen Argent

August 2017