Inspiring Older Readers

posted on 10 Jul 2017

posted on 10 Jul 2017

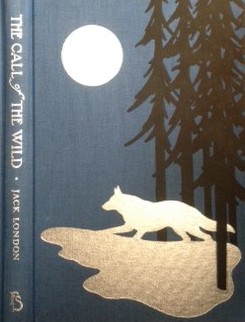

Call of the Wild by Jack London

Jack London can claim to be one of the most idiosyncratic novelists of the late 19th and early 20th century – journalist, social activist, short story writer, novelist and even, by all accounts, oyster pirate. He lived hard, burned brightly and died young – he was just 40 when he succumbed to multiple complications arising from long term illness. He earned his reputation the hard way with George Orwell famously noting that ‘he was an adventurer and a man of action as few writers have ever been’. But he was also a prolific writer like few others have been, with novels, short stories, poems and plays running into the hundreds and a substantial amount of non-fiction – much of it in support of his, then unconventional, Socialist views. Although there is some doubt about whether it can be wholly attributed to him, the so-called Jack London Credo does capture the essential philosophy of the man:

I would rather be ashes than dust!

I would rather that my spark should burn out in a brilliant blaze than it should be stifled by dry-rot.

I would rather be a superb meteor, every atom of me in magnificent glow, than a sleepy and permanent planet.

The function of man is to live, not to exist.

I shall not waste my days in trying to prolong them.

I shall use my time.

This essential spark of life that burns so brightly in London also made him acutely aware of nature and he developed an almost Pantheistic understanding of the natural world. This empathy for the wild and the natural animates what is probably his most famous and still most popular book – The Call of the Wild. It is, in many ways, an extraordinary piece of work and an astonishing feat of imagination that is written in London’s trademark style – simple and direct without recourse to complicated parenthesis or unnecessary embroidery. It tells the story of the dog Buck, stolen from his domesticated home in California, traded to become a sled dog in the Yukon and often brutally used by a series of more or less competent and incompetent owners before finding some kind of peace in returning to his wild heritage as a member of a wolf pack. But what makes the story unusual is that it is told through the eyes and from the perspective of Buck himself. London so thoroughly anthropomorphises the dog that there are times it’s possible to forget that he’s not human.

We are spared nothing by London as he tells us the tale of how Buck – a big, brave natural leader – is broken and set to work. We see the savage struggle for power between dogs as the jostle for pack dominance and we see the casual indifference and brutality of their human owners. London is brilliant at showing how Buck is transformed by the wilderness from domestic pet to elemental animal, driven by urges that date back to the dawn of man and the beginnings of the domestication of the wolf.

Buck’s bravery isn’t all about survival though – he sacrifices himself for loyalty when he is shown love. Having been saved from almost certain death at the hands of stupid and inexperienced owners by John Thornton, Buck pledges himself completely to the man and saves his life on at least two occasions. But, when Thornton is killed by a group of rogue native Indians, Buck’s ties to civilisation are finally cut. He takes revenge on the Indians, killing indiscriminately, before running off to join a local wolf pack. His name lives on as the Ghost Dog of the Northern legends.

Published in 1903, the book was an instant hit and helped make London a wealthy man. In 1906 he published what can be seen as a companion piece to this, White Fang, in which he repeats the trick of using the dogs-eye view of the world.

London’s powerful knack for storytelling, his empathy for the dogs and his remarkably accessible style has made him an author capable of crossing over from an adult audience to the children’s market with ease.

Call of the Wild is one of those singular books that is little longer than an extended short story and yet, when you’ve finished, makes you feel that you’ve just read a substantial novel. That’s the mark of a fine writer who doesn’t have to go out of his way to show just how good he is.

Terry Potter

July 2017