Inspiring Older Readers

posted on 11 Jun 2017

posted on 11 Jun 2017

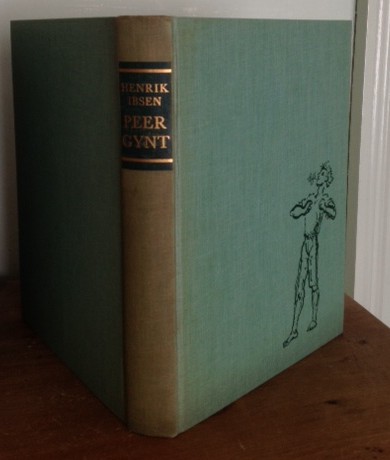

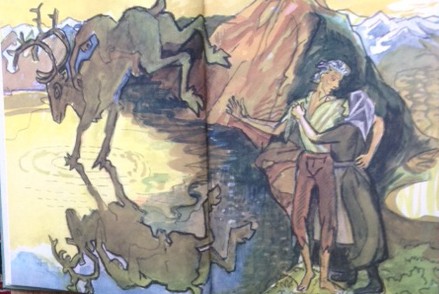

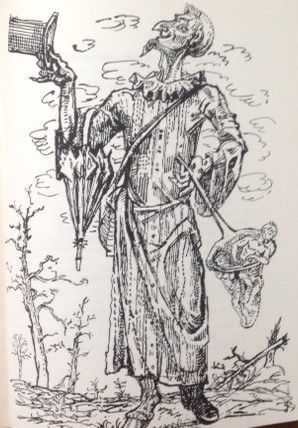

Peer Gynt by Henrik Ibsen illustrated by Per Krohg

I actually first came to read Ibsen’s Peer Gynt as a result of hearing Grieg’s famous suite of music which was written as incidental accompaniment for the verse play. The music is extraordinarily evocative and pictorial and gave the 17 year old me a real desire to read the play.

Published in 1867, Peer Gynt is a five act verse play which takes traditional Norwegian fairy tales as its inspiration – territory that was completely different from any other plays of Ibsen’s I’d read, all of which seemed to be firmly in the tradition of modernist or realist tragedy. As I came to discover later, Peer Gynt is not Ibsen’s first or only verse play but it is by some distance the most famous. However, the first time I tried to read it I found it quite difficult to stick with – possibly because the unfamiliarity of the Norwegian myths made it quite difficult for me to tune into.

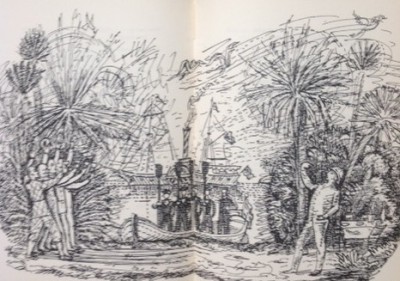

The play which takes its picaresque hero on a journey from the Norwegian mountains to the deserts of North Africa has been widely praised by critics as a satire on the Norwegian identity. Lazy, disrespectful and a braggart, Peer is also a force of nature and oddly loveable. But there are plenty of other critics who have been less complimentary and who have been puzzled by the choice of verse as the medium – in particular they question the quality of Ibsen’s poetry. Despite this, the author fiercely defended his creation and rightly predicted it would come to be hugely influential.

The fantastical nature of the plot seemed at the time to make the play almost impossible to stage but overcoming the challenges Ibsen sets the theatre director or producer has in fact had a lasting influence on what we see in theatre and on the art of playwriting.

Years after first trying to read the play I went back to it and found that understanding some of the background to the play and grasping more fully what Ibsen was trying to do made me much more amenable to it – and I loved it. Sadly, though, I’ve never had a chance to see a production of the play and I’ve had to make do with the book version and Grieg’s marvellous music.

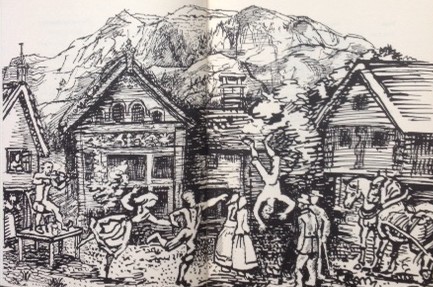

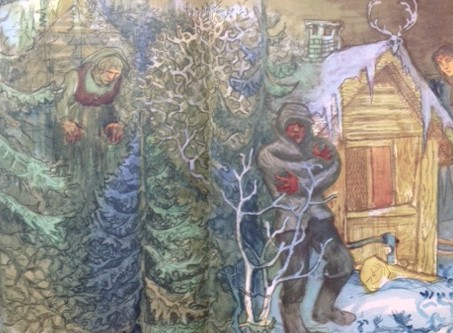

This edition of the play published by the US-based Heritage Press in 1956 is one of the more sumptuous editions I’ve come across. It’s illustrated by Per Krohg, himself a Norwegian, is perhaps most famous for producing the mural that can be seen in the United Nations Security Council Chamber and frescos in the University of Oslo and in Oslo City Hall.

Krohg spent some time studying art under the tutelage of Matisse and I think that influence is immediately obvious in the illustrations that can be found here. There are several double page colour spreads and a whole host of black and white drawings scattered through the play.

The translation of Ibsen’s work is a notoriously contentious field and the Ibsen Society of America has a fantastically comprehensive list of those who have had a stab at it. The text here has been translated by William and Charles Archer who also provide the very useful introduction but I’ve no idea how highly this is thought of by scholars – but it doesn’t seem too bad to me.

Copies of this edition are quite hard to find in the UK and you might have to ship a copy over from the States – which will add to the cost of getting your hands on the book. You should still be able to get one for not much more than £20.

Terry Potter

June 2017