Inspiring Older Readers

posted on 09 May 2017

posted on 09 May 2017

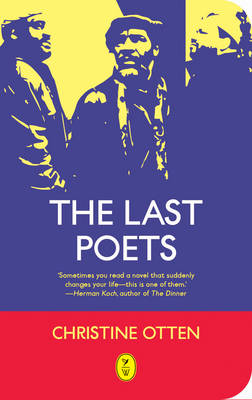

The Last Poets by Christine Otten

Dutch writer and music journalist Christine Otten is completely in thrall to the legend of The Last Poets, the fabled creators or ‘godfathers’ of what we now think of as the rap and hip-hop scene. Writing about her fascination she has said:

When I first met Umar Bin Hassan and Abiodun Oyewole, two of the founding members of the legendary Last Poets, a decade ago in New York, I wasn’t planning on writing a novel based on their lives. I had heard about The Last Poets, through my 11-year old son, who was a hiphop fan. I’d learned they were considered the ‘Godfathers of hiphop’. That they had shocked white and black audiences all over the world in the late sixties/early seventies with militant poems like ‘Niggers Are Scared Of Revolution’. They had been famous all over the world. After years of personal struggle, The Last Poets were performing again and I was going to interview them for a Dutch newspaper. ‘Who are you, what do want?’ I remember Umar mistrustfully saying on the phone. ‘I admire your poetry,’ I answered. Umar made me promise to pay his bus ticket from Detroit to New York. The next day we met in Abiodun’s flat in Harlem. From that moment on, I was completely absorbed by The Last Poets’ lives, stories and poetry, which reflect the recent history of black America.

What Otten has done here is to try and break down the boundary lines between the novel and the biography, between fiction and interview. Traditional approaches to musical profiles or biographies focus more on background, the musical apprenticeships, the inevitable profile parabola from struggle to success to disintegration. No so with this one. Otten uses fiction to recreate the backgrounds of the band members, to draw out personality and try to explain motivation and action. Mixed in with this are interviews with band members, record producers, sound engineers and personal friends whose words dovetail into the story of four men at the centre of a political storm and who are busy stirring that storm with their music and words.

It’s impossible to take The Last Poets out of their political context – they are a manifestation of the prejudice and discrimination that continues to shape the lives of Black Americans. Their songs – raps – articulated the militant expression of black anger during the fight for Black civil rights in the 60 and 70s and always attracted controversy within black and white communities – often for quite different reasons. However, it would be a mistake to think of the Last Poets as a specific group of people – the name was more a brand that was constantly being reinvented by different personnel moving in and out.

Otten’s book imagines the Last Poets when their membership consisted of Uman Bin Hassan, Felipe Luciano, David Nelson and Abiodun Oyewole and each of them is given their own unique storyline. Inevitably a good deal of the focus of the book is on the tensions, the strains, the disappointments and the frailties – drug taking, sex and violence in particular. And this is where I started to feel uneasy about Otten’s project. It began to feel to me that her obsessive fascination in The Last Poets might have its roots in the perverse and sordid rather than in the revelatory and celebratory. For me there was far too much of a concentration of the visceral private lives of the poets – the sex was always pungent and slightly grubby, the drugs alluring, the arguments vicious.

And although lyrics or poems are scattered throughout the book to introduce or end chapters I found myself wanting to know more about the words and music, more about their impact on the political scene; I wanted to have a glimpse of some of the success and joy of being a ground-breaking musician at a crucial moment in history. But Otten gives us precious little of that.

What I don’t see here is anything much about legacy – about what the work of The Last poets enabled. Otten herself has said:

Inspired by the music of John Coltrane, the glamour of The Temptations and the political message of Black Pride, they started out performing on street corners in Harlem. They inspired David Bowie, Mick Jagger, Mos Def, Common, Erykah Badu and Public Enemy, to name just a few.

But I’m not sure you’d take this message away from the book. Otten seems uncomfortably fascinated in an almost voyeuristic way with the world she is both describing and creating and somewhere in all of this I can’t shake the feeling that something quintessential has been lost – the soul of the Last Poets.

Terry Potter

May 2017