Inspiring Older Readers

posted on 17 Jan 2017

posted on 17 Jan 2017

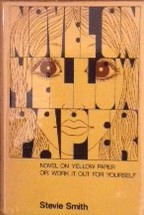

Novel on Yellow Paper by Stevie Smith

In a rather lazy way I’ve always thought of Stevie Smith as a kind of British Dorothy Parker – which I think turns out to be both a little bit true and quite a lot false. Born in 1902, I have tended to associate Smith with a sort of pithy, world weary poetry shot through with a devilish wit – hence, I think, why I associated her so much with Parker. However, her career as a poet is in fact foreshadowed by her first attempt at novel writing, Novel On Yellow Paper published in 1936.

I know that Stevie Smith’s work and this novel in particular have fervent admirers and when I was at university in the early 1970s she was being rediscovered by many of the women who were in my social circle at the time. By the end of that decade there had also been a film, Stevie, with Glenda Jackson taking the title role but beyond a smattering of her verse, I hadn’t read anything.

Novel On Yellow Paper had been reissued in the hardback you see pictured on this page in 1969 by Jonathan Cape and it has sat on my shelves, unread, for the best part of thirty years. I was reminded I had it when I was recently hunting for the origin of the famous Not Waving But Drowning poem I wanted to use for a lecture and turned up my copy of the book. So, I thought, I still haven’t read you but don’t despair, your time has finally come.

In form and presentation this is a remarkable book for its time. It is, I think, heavily influenced by Virginia Woolf’s experiments with prose form – there is a kind of stream of consciousness at work here as we see everything happening through the eyes and consciousness of the central character, Pompey Casmilus, the flighty and gossipy secretary to Sir Phoebus Ullwater, director of a magazine empire. Pompey is also busily also recording her feelings and experiences on the office stationery – hence the novel on yellow paper – but unlike Woolf who uses her books to probe the surfaces of the real and the unreal, Stevie Smith’s prose seems to be in love with everything modern, immediate and concrete. Pompey, like her boss, is astonishingly superficial and in danger of becoming bored with everything at any minute.

Although much of the ‘story’ is taken up with Pompey’s on/off love affairs with Karl and Freddy, Smith also allows us to see the rise of German nationalism through Pompey’s eyes – something which the historical perspective we can now have should make us re-evaluate just what the author was trying to do back in 1936 when this book was published. There is an undeniable melancholy that permeates the book despite the breathless narrator shifting us along at the gallop and in this there is something that captures the essential spirit of the inter-war years.

The danger with a book like this is that you have to be able to identify at some level with the central character otherwise you become either alienated, irritated by them or simply indifferent. I was swept along and intrigued by the first third of the book but I have to confess that both indifference and irritation set in after that. Smith’s second novel vanished without trace while her reputation as a poet grew – I think I see why.

Terry Potter

January 2017