Inspiring Older Readers

posted on 28 Jul 2016

posted on 28 Jul 2016

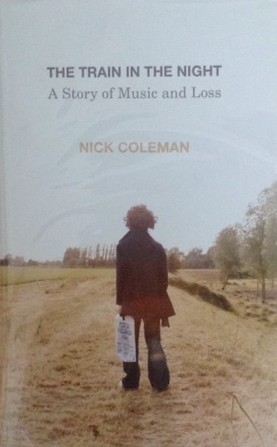

The Train In The Night by Nick Coleman

What must it be like to suddenly go completely deaf in one ear? Not only that but to find you can’t move your head without vomiting and having a set of roaring, glooping and clanking noises filling your skull until you think you might explode? What’s it then like to find no-one is offering any sort of cogent idea about what has happened and how long it might last? And if there is no help or rehabilitation available? Well, Nick Coleman’s excellent memoir might give you some idea of what that nightmare journey might be like..

But that’s only half the story here because Coleman’s whole life has been built around music – and now he can’t bear to listen to it. As a music journalist for NME, Time Out and The Independent that sounds like a real problem but it goes deeper than his effectiveness in a job – from his early teens music has literally been his life and the core of his identity.

So this book takes us on a journey through two stories that find themselves running side-by-side with each other – the story of a distressing and mysterious illness and the story of how music formed a young man in the adult he became. Fascinating and disturbing as the medical story is, it plays second fiddle to the story of his musical journey. And you can feel this in the writing too – Coleman is clearly angry and perplexed by his illness and he writes about it with exceptional honesty and clarity but when he starts recalling his evolution as a music fanatic, the prose really does take flight and the book moves into another dimension.

Early on in his illness Coleman realises that he has to start ‘experiencing’ music in a completely different way. Eventually he will be able to physically listen to it again but in a way he would never have imagined – quietly, often attached to a visual stimulus and with the aid of his memories. He is forced by these circumstances to reassess what the music he knows so well means to him – to try and locate the music not so much in the outside world of aural stimulation but the internal world of remembered emotions.

Terrible as his story is, there’s plenty of humour here. He is sometimes direct to the point of bluntness but the affection he has for his younger self and his friends is also evident. Coleman found himself in the ‘freak’ camp when it came to music – by which he means he became an aficionado of progressive (prog) rock acts like Genesis, rock monsters like Led Zeppelin and the Rolling Stones. Being seen to be part of this tribe was as important, if not more important, than the music itself. Loyalty to your chosen music was the key and in semi-rural East Anglia these affiliations took on life-changing dimensions.

The interface between music and girls also loomed large – clearly he had significantly more knowledge of music than he did women – and it is his non-relationship with Lulu, the object of his desire, that he will eventually use to tie together the boy and the man, the music and the illness.

I very much enjoyed this book because it spoke to a musical environment I could recognise quite intimately. Coleman is half a dozen years younger than me but his musical influences were ones I could easily relate to and his description of his fanatical obsessions were truthful and recognisable to anyone who had flirted with the same world.

I felt in the end that book was maybe 50 pages too long and the device of using an unrequited fascination with a girl to comment on his relationship with music and what it meant to him didn’t quite work for me – it felt contrived. I read the book in a couple of afternoons and thoroughly enjoyed the experience – although that might not be quite the best word when you consider it is a book built around the poor man’s suffering.

Terry Potter

July 2016