Inspiring Older Readers

posted on 29 Jun 2016

posted on 29 Jun 2016

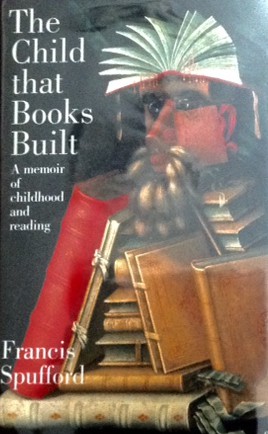

The Child That Books Built by Francis Spufford

Spufford sub-titles his book ‘A memoir of childhood and reading’ which really doesn’t capture either the complexity or charm of this book. In some ways it’s an odd mixture of different things – some part academic study of how reading is acquired and subsequently influences development; some part childhood memoir; and, some part a wholehearted plunge into the favourite books of his early years.

Not all these separate parts are entirely successful nor do they all integrate as smoothly as they might. Probably the least well realised aspect of the book is the personal memoir element which relies on hints and suggestion rather than full-blown personal testament. We get quite a tantalising picture of a boy who feels isolated within his family because of the overwhelming influence of his sister’s debilitating illness and the way he uses books as a mode of escape. Towards the end of the book we discover his sister died by the time she reached her early 20s and again we get only a brief glimpse into how this terrible reality shaped his attitude to reading. I couldn’t help but feel there was a whole other book here waiting to be written and the fact that he clearly doesn’t feel quite able to open up this facet of his life and mental state does, in my view, slightly undermine his core intention in writing this book in the first place.

However, I don’t think this criticism spoils the enjoyment of the book as a whole. His ability to blend some very complex academic material on the acquisition of language and reading into a completely accessible narrative is done skilfully and without unnecessary detail. He keeps the book moving along at a good pace and doesn’t let theory get in the way of understanding.

By far the most entertaining parts of the book are when he opens up and leaps into unfolding the books that clearly entered deep into his soul. For me, his analysis of his obsession with the C.S. Lewis Narnia series is outstanding – perceptive and shot-through with humour. The adult Spufford looks back at his Narnia fixation and tries hard to understand what it was that drew him in but with the added perspective of a critical take on some of the more dubious aspects of the religious allegory Lewis grafted onto his story.

In many ways it is the fantasy genre that binds his reading life together; fairy stories lead him on to the Hobbits of Tolkien, the Earthsea of Ursula Le Guin and Lewis’ Narnia. Ultimately, this will culminate – seemingly inevitably – in a teenage fascination with science fiction. There is also the confession of a flirtation with pornography which is, of course, the adult branch of the fantasy family.

I really enjoyed the book when I first read it several years ago and returning to it now I found it a much richer – if more flawed – experience. However, I would say that this is a must-read for anyone interested in children’s literature, either from an academic perspective or simply because you want to follow an excellent writer as he explores his reading history.

Terry Potter

June 2016