Inspiring Older Readers

posted on 07 Jun 2016

posted on 07 Jun 2016

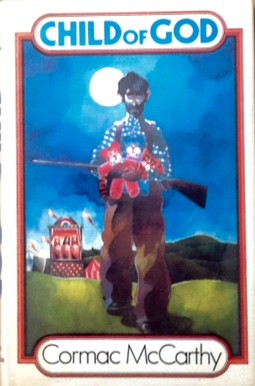

Child of God by Cormac McCarthy

Who is the greatest living novelist in the US? I realise that's probably a stupid question and almost impossible to answer in a meaningful way but if I was forced to make a recommendation I think my vote would go to Cormac McCarthy. I have to confess he's not an easy option - his subject matter is often genuinely shocking and he writes in such a spare, paired-down style that it can often make you feel almost physically assaulted when you finish one of his books.

Even with books as shocking and unnerving as Blood Meridian, Suttree, The Road and No Country For Old Men in his repertoire, Child of God is an extraordinary visceral experience. The book documents the short and squalid life of Lester Ballard living in Tennessee in the mid-1960s. The story opens with Ballard being evicted from his family homestead and abandoned to wander the countryside finding what cover he can and trying, but failing, to make contact with other human beings.

Lester's spiral downwards to ultimate degradation is set against the turning of the seasons over a year. Cast into a countryside that is indifferent to his needs, Ballard slowly turns feral and increasingly predatory. He descends, literally, into the caves of the earth and morally into a miasma of murder and necrophilia.

McCarthy sets out the path of Ballard's decline without needing to engage in explicit judgement of his actions. Nor does he seek to explain his actions.Ballard isn't set up to be seen as evil or an animal but neither is he given excuses. Brief flashbacks within the narrative show us how Lester was set on a path from childhood when his family disintegrated around him and as a child he witnesses death and suicide.Equally, Ballard is the architect of his own misfortunes - driven by his own sense of self-righteous injustice, his disregard for the feelings of others and need for sexual gratification. Ultimately his trail of murder inevitably leads to his downfall and his end is as ignominious as his life.

McCarthy writes in a seemingly simple yet elemental way. The books are packed with symbolism that doesn't beat you over the head but provides a vital superstructure for his extended morality tales. It's impossible in this novel to ignore the references to biblical imagery - both Old and New Testament. It's possible to read Ballard's plight as a savage retelling of the expulsion of man from Eden. Ballard, it can be argued, is an everyman, an Adam or anti-Adam, in that he is capable of every degrading act that humans harbour in their psyche. He moves from a state of relative human grace to inhuman troglodyte and, even after his death he descends into his component parts - a sort of organic gloop. In all of this, nature and the universe remain steadfastly indifferent, moving inevitably around its seasonal cycle unchanged by the human comedy.

In this short novel - less than 200 pages - McCarthy packs extraordinary power and depth. His stripped back style makes every word work to its full potential and by the end I felt I'd witnessed something almost visionary in its execution.

Copies of the book are easy to get cheaply in paperback but, like all his early novels, the first editions a punishingly expensive to buy. It might tell you how highly I think of this book if I say that I recently purchased an idiotically costly copy for my collection.

Terry Potter

June 2016