Inspiring Older Readers

posted on 10 Apr 2016

posted on 10 Apr 2016

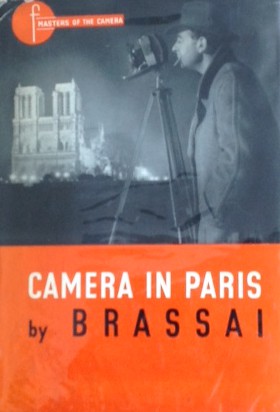

Camera in Paris by Brassai

I was really fortunate to stumble across this 1949 copy of the Focal Press edition of Camera in Paris not so long ago in a second hand bookshop - where I was able to get it for a steal. These early editions of some of the great photographers are really quite hard to find and so I didn't hesitate.

Brassai was the name taken by Hungarian artist, Gyula Halász, who came to live in Paris in the inter-war years and took the name Brassai from his home town of Brasso - which is now actually part of Romania but had been Transylvania in the old Austro-Hungarian empire. He arrived in Paris in 1924 at the age of 25 and immediately became part of the artistic Bohemian communities - he knew Picasso, Braque, Miro, Dali and Henry Miller. He considered himself close enought o Miller to write a biography of the man although Miller's own private papers suggest he wasn't as keen on Brassai as this might suggest.

To earn a living Brassai became a journalist and started to use photography as an aid to his job - although up to this point he had little sympathy for photography as an emergent art form. However, it turned out to be the perfect medium for his talents and for his own vision of his adopted city. With his camera he became a feature of the Paris landscape and was especially drawn to some of the darker, seedier elements of the city that he set about documenting. His first collections came out in the mid-1930s and were typified by his desire to showcase the Paris nightlife in all its glory. When war broke out and street photography became impossible, Brassai returned to his other art forms - especially sculpture, drawing and - more unusually - poetry. When the war ended however he returned to photography and his work became more static and more posed.

He had his first major retrospective in 1968 and died in 1984. For me Brassai is the distilled essence of the edgy Paris that attracted so many artists and writers between the wars - he does not shy away from prostitutes or homosexuals and photographs them with real understanding - Brassai's photographs never feel patronising or voyeuristic because he is part of the city and not an outsider looking for local colour.

This book is not a big bucks production and there are only smallish plates by comparison with the big productions that come along later. However, somehow, these rougher, less glossily produced prints feel more authentic and closer to the real spirit of the man.

Terry Potter

April 2016