Inspiring Older Readers

posted on 14 Feb 2016

posted on 14 Feb 2016

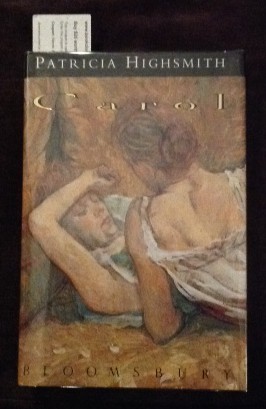

Carol by Patricia Highsmith

Over the past month several people whose opinions I respect have told me that the recently released movie of Carol is a fabulous, rich experience. I haven’t seen it yet and now I’m wondering if my decision to read the novel means I won't be able to bring myself to see the film version.

Highsmith originally published the book in 1952 under the title The Price of Salt but had to do so under a pseudonym because of the restrictive social codes of the day that made it impossible for gay relationships and gay sex to be openly talked about and for gay authors to write about the subject. The novel was, however, popular amongst lesbian readers in particular and not just because of the detailed and unapologetic portrayal of a lesbian relationship but because – and this was unusual in this sub-genre – the novel had a ‘happy’ ending. It’s probably fairer to say it didn’t have an unhappy ending but whether there is a happy future for Carol and Therese is left as more of a possibility than a certainty.

The story of the book is really very simple. Therese a 19 year old stage set designer is waiting for her career to take off and has taken a soul-destroying job in a big department store. One day Carol comes in as a customer and Theresa finds herself entranced by her beauty and poise. Ultimately the two women forge a friendship and, eventually, an emotional and physical relationship. There are, however, barriers that have to be overcome. Therese is involved with Richard, a young man from wealthy family who is looking for a purpose and has attached himself to the idea of being a great painter – something she knows he will never become much in the same way as she knows she will never love him. Carol is older and has a husband and daughter – a messy divorce is in progress which will become central to the story.

Carol and Therese decide to take a road trip to spend time together and to escape their circumstances. However, Carol’s husband, Harge, employs a private detective to follow them and get evidence of their sexual relationship to use against her in the courts. Fearing she will lose all contact with her daughter Carol abandons Therese but they are eventually bought back together again and – it is hinted – in a relationship that will be even stronger the next time around.

The power of this book lies in the characterisation and the truthfulness of the emotions. Not only are the individual personalities of Therese and Carol beautifully and subtly drawn, changing and developing as the novel progresses but so too are is the cast of secondary figures – Richard in particular is a vivid creation and although Harge appears only briefly his shadow looms over the two women as they become more and more deeply committed to each other.

Thankfully there are no excruciating sex scenes although Highsmith doesn’t dodge intimacy or even erotic physicality – she is simply too good a writer to be crude or embarrassing. It is, in fact, her ability to handle physical detail that is so impressive and which makes the novel such a vivid experience. I feel I know these people and that I have seen inside their houses, flats, motels and bars and it is this that makes me cautious about seeing the movie. Making a film of a book always involves compromise and when you’ve engaged with such a visceral writer as Highsmith can be at her best, cinematic versions simply can’t compete with the readers own imagination.

Terry Potter

February 2016