Inspiring Older Readers

posted on 07 Feb 2016

posted on 07 Feb 2016

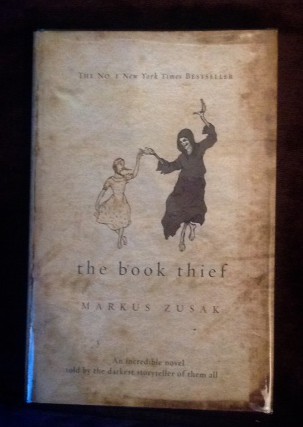

The Book Thief by Markus Zusak

When the book was published in the UK in 2007 it was on the back of quite a lot of hype and in the wake of plenty of very favourable reviews. I bought a copy and it joined the ‘waiting to be read’ pile. It never made it out of that heap and I eventually slipped it onto a shelf where it’s sat ever since.

Eight years later as I was grazing for something a bit different to read, there it was winking at me. Now having read it, what a complete chump I feel to have waited so long. The rave reviews were deserved I think and this really is a substantial novel by anyone’s standards.

The book was seen as unusual or even controversial for several reasons that are worth putting right up front:

· Is this a book for adults or older teenagers? Well, despite the harrowing and tragic nature of the tale I am convinced it’s a book a teenager could easily find themselves loving and getting genuinely involved with – but equally, its adult themes make it a book for older readers too with complex layers and some important political messages.

· Yes, it’s long. Almost 600 pages. While it’s a story that deserves an extended treatment, I think I would argue that it is over-long and a bit of careful editing would have helped give momentum to the story which tends to flag about two-thirds of the way through.

· Yes, it’s a story of the Holocaust but actually it’s much more than that. This is a tale of how the Nazis not only destroyed the lives and futures of their victims but unpicked and brutalised the lives of ordinary German citizens who were unable to resist the Party machine.

· And, yes, it’s a story told by Death. It’s not, of course, the first to use a personification of Death to tell a tale but the use of this allegorical device here gives the story a sense of inevitability and tragic grandeur.

Death finds himself fascinated and entwined in the life and adventures of Liesel Meminger, a young girl who is effectively orphaned when her Communist parents fall foul of the emerging Nazi Party. She is relocated to a small town in Germany called Molching and to the home of Hans and Rosa Hubermann in the impoverished Himmel Street. She develops a deep attachment to the caring and kind Hans and eventually to Rosa too despite her brusque and often waspish tongue.

But the story of Liesel really revolves around three big events in her life – her friendship with and eventual love for Rudy, the arrival of Max who is a Jew on the run from the Nazi regime and becoming the thief of the book’s title. I don’t intend spelling out how all these issues bind together in the book because that would spoil the reading experience but there is one thing I can tell you without risk of it being a spoiler – everyone dies in the end. However, when they die and how they die is never obvious or predictable and Death keeps telling us little misleading half truths about his role throughout.

Of course Death has been around to see the madness of war before but somehow the story of the little girl in Germany who couldn’t read but eventually becomes the book thief of the title allows Zusak to show us just how dehumanising ideologies can be but also just how fearfully cruel the human species are when fear, suspicion and irrationality take over.

The narrative shape of the book and the device of using Death to structure the story from his point of view requires the reader to shift perspective and it might take you a few pages to tune into what’s going on here. But stick with it because the book is a triumph.

Terry Potter

February 2016